Understanding CISSP Domain 6, Security Assessment and Testing - Part 1

Through the first five domains, we’ve explored a wide range of controls designed to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of systems and data. Technical controls play an important part, but once they’ve been configured and deployed, they need to be regularly assessed and tested to ensure they’re working as intended and delivering real security program value.

That’s where security assessment and testing programs come in. These strategies help perform systematic checks to verify that the right controls are in place and functioning effectively.

In this domain, you’ll gain a solid understanding of the tools and methodologies used by security professionals to assess and validate security controls, an essential part of maintaining a strong security posture.

In Part 1, we’ll cover objectives 6.1 and 6.2, designing and validating assessment & audit strategies, and conducting control testing.

Let’s dive into the domain and cover the material by continuing to follow the ISC2 exam outline.

6.1 - Design and validate assessment, test, and audit strategies

Security assessment and testing programs identify vulnerabilities, measure risk levels, and determine how well existing security controls protect against potential cyberattacks. These programs are crucial for proactively mitigating security risks, ensuring compliance with industry regulations, and protecting an organization’s reputation and data.

An assessment and testing program includes regular assessments and audits verifying that controls are working as intended.

Designing and validating effective security assessment, testing, and audit strategies means using a risk-based approach that aligns security efforts with business objectives and compliance requirements.

A security assessment is a systematic and comprehensive evaluation of an organization’s security posture to identify potential risks, threats, and vulnerabilities in assets and systems. An assessment can be conducted by an internal team or a third party, and the main deliverable is an assessment report.

A security audit uses the same techniques as a security assessment, but is performed by independent auditors. An audit is a more formal process that tries to objectively verify if the organization is adhering to specific security policies, established industry standards, or regulatory requirements.

When prioritizing security testing efforts, weigh several critical factors to allocate resources effectively and minimize risk. Key considerations include logistical constraints such as the availability of testing resources, the difficulty and time required to perform a test, and the potential impact of the test on business operations.

Try to take into account the risk profile of the assets under review, for instance, the criticality of systems and applications, and the sensitivity of the information they manage. Keep in mind that assessments need to factor in internal risks, such as the likelihood of technical failures or misconfigured controls. External risks also need to be considered, such as the likelihood of the system being attacked. The rate of technical change affects a security program in many ways, including the need to have a flexible, risk-adaptive testing strategy.

Internal (e.g., within organization control)

Internal audits are done by internal staff who are usually independent from the parts of the organization they are evaluating. Internal audits are usually intended for internal staff.

Security metrics and reporting are a fundamental component of internal auditing, providing the data-driven evidence necessary to objectively evaluate the effectiveness of security controls, evaluate budget changes, ensure regulatory compliance, and inform risk management decisions.

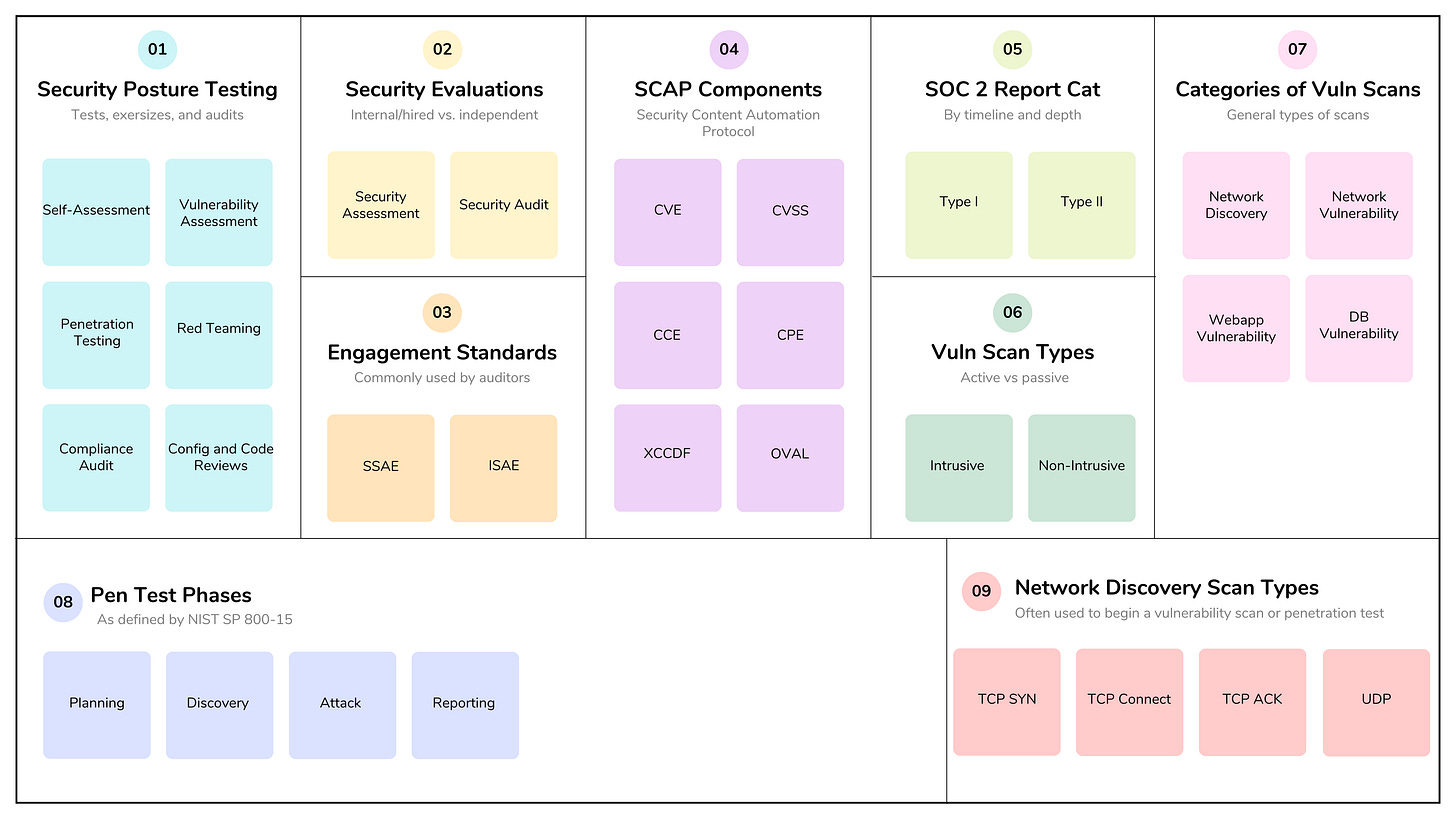

Companies use a variety of internal exercises and tests to proactively assess their security posture across technology, people, and processes. These exercises focus on identifying and exploiting vulnerabilities within the organization’s systems and infrastructure:

Self- Assessments: Evaluation by departments or teams used to gauge internal security practices. Self-assessments can be used for gap analysis, comparing the current state or practices against targeted goals, or for assessing readiness for an external audit.

Vulnerability Assessments: Scanning networks, systems, and applications, often using automated tools, to identify known weaknesses, misconfigurations, and missing patches.

Penetration Testing: Security professionals (ethical hackers) simulate real-world attacks in a controlled environment to find and exploit vulnerabilities, demonstrating the potential impact of a breach.

Red Teaming: A more comprehensive, covert exercise than a typical penetration test, where a dedicated team attempts to achieve specific objectives (e.g., accessing critical data) using any means possible. The goal is to test the effectiveness of the organization’s detection and response capabilities without the internal teams’ prior knowledge.

Breach and Attack Simulation (BAS): BAS platforms automate the continuous simulation of real-life attack scenarios against existing security controls to measure their effectiveness and identify immediate gaps in prevention and detection.

Configuration and Code Reviews: Detailed inspections of system configurations and source code to ensure they align with security best practices and are free of errors.

When conducting internal security assessments, key considerations revolve around ensuring objectivity, maximizing efficiency, and translating technical findings into actionable business outcomes.

Define Clear Objectives and Scope: Clearly outline what the assessment aims to achieve (e.g., test incident response readiness, ensure compliance with a specific regulation) and precisely define the systems, networks, or business units included. An overly broad scope can dilute efforts, while a too-narrow one may miss critical vulnerabilities.

Align with Business Goals and Risk Appetite: Ensure the assessment priorities align with the organization’s strategic objectives and risk tolerance. Focus resources on protecting the most critical assets first.

Ensure Objectivity and Independence: Internal teams may be too familiar with existing systems, leading to blind spots or unconscious biases. They also need to be free of any potential internal conflicts or political fallout from the reported test results. Mitigate these concerns by creating independent internal audit teams or bringing in external experts periodically for a fresh perspective.

Prioritize Risks for Action: Don’t just provide a list of vulnerabilities. Use a risk matrix to score issues based on likelihood and potential business impact. This helps management to focus on the most critical risks first.

Develop an Actionable Remediation Plan: Ensure findings are tied to concrete, assigned remediation actions with clear ownership and realistic deadlines. The assessment is only valuable if gaps are closed.

External (e.g., outside organization control)

External audits and testing are performed by third-party firms with no direct affiliation and no (theoretical) conflicts of interest with the organization. Although they are under the control of the requesting organization, they provide an independent and objective assessment of a company’s security posture.

Some examples of external audits and testing include security assessments, compliance audits, and external penetration tests. When engaging an external firm for a security audit or assessment, the process should involve careful planning, execution, and follow-up.

Vendor Selection: It’s important to find a third-party auditor with expertise and market credibility in the required areas.

Define Objectives and Scope: The organization and the external firm should collaboratively define the objectives (e.g., meeting HIPAA compliance, identifying technical vulnerabilities) and the specific scope of the engagement and access to resources.

Managing the Scope Creep and Resources: While the scope should be well-defined upfront, be prepared to allocate sufficient internal resources and time to support the external firm’s inquiries and requests.

Develop an Actionable Remediation Plan: As with internal remediation, ensure findings are tied to concrete, assigned remediation actions with clear ownership and realistic deadlines.

Third-party (e.g., outside of enterprise control)

Third-party audits are conducted on behalf of another organization, such as a regulatory body or customer, to meet compliance or contractual obligations. Since the auditors are selected by the initiating third party, the organization has little control over the audit. Organizations that provide client services are often audited, and the audit process can indeed be burdensome if they have many clients.

To reduce these burdens, standards such as the Statement on Standards for Attestation Engagements (SSAE) 18 (“Attestation Standards: Clarification and Recodification”) and International Standard on Assurance Engagements (ISAE) 3402, (“Assurance Reports on Controls at a Service Organizations” — outside of the US) serve as a common standards that auditors can use instead of requiring multiple third-party assessments.

SSAE and ISAE engagements are known as system and organization control (SOC) audits:

SOC 1: Focuses exclusively on controls that impact a client’s internal control over financial reporting. It is typically required for service providers like payroll processors or loan servicers whose work directly affects a customer’s financial statements.

SOC 2: Evaluates security (confidentiality, integrity, availability) and privacy of systems. It is the standard for technology providers, cloud services, and SaaS companies that store or process customer data. Results are confidential, and audited companies require customers to sign an NDA to receive a copy.

SOC 3: A high-level, public-facing summary of the findings from a SOC 2 audit.

SOC 2 reports are categorized into two types based on their timeline and depth:

SOC 2 Type I: A snapshot that assesses the design of controls as of a specific date. It is faster to complete and verifies that controls exist, but it does not test if they actually function effectively over time.

SOC 2 Type II: The “gold standard” that evaluates both the design and the operational effectiveness of controls over a period of time, typically 3 to 12 months. It requires detailed evidence and sampling to prove controls worked consistently throughout the period. Type II reports are considered more reliable than Type I.

For the exam, note that the three types of audits are differentiated by who controls them:

Internal audits are under the organization’s control.

External audits are conducted by a third-party, but they are hired by the organization.

Third-party audits are conducted by a firm that is hired by another company, and thus are outside the organization’s control.

Location (e.g., on-premises, cloud, hybrid)

The location of an organization’s infrastructure, whether on-premises, cloud, or hybrid, significantly impacts the challenges and strategic considerations for security assessments, testing, and audits.

1. On-Premises Infrastructure

Assessment and audit strategies for on-site infrastructure focus on full-stack ownership and physical access.

Considerations:

Resource Burden: Be aware that evidence collection and reviews can be labor-intensive. They can consume time and limited funds for organizations with limited staff resources and budget constraints.

Physical Access and Scope: Audits may require physical access to systems, hardware, and data centers, and the fact that the organization has complete access to infrastructure and security configurations may increase an audit’s scope.

2. Cloud Infrastructure

Testing in the cloud is governed by the Shared Responsibility Model, where the provider secures the “cloud,” and the customer secures everything “in” the cloud.

Considerations:

Right-to-Audit: a contractual provision that grants a customer the authority to verify their cloud service provider’s (CSP) compliance with security, operational, and regulatory standards. Because customers normally can’t physically inspect cloud data centers, this is a critical mechanism for traceability and transparency in the shared responsibility model.

Reliance on Provider Documentation: Due to the lack of physical access, modern cloud audit rights typically provide for documentation access and performance metrics. Auditors and organizations often rely on third-party assurance and audit reports (e.g., SOC 2 Type 2, ISO 27001), but auditing challenges persist in understanding how customers use services and APIs and in identifying potential configuration issues.

3. Hybrid Infrastructure

Hybrid environments combine on-premises and cloud, creating the highest level of complexity for auditors.

Considerations:

Inconsistent Policies: Maintaining uniform security standards across disparate environments can often lead to blind spots and increased audit challenges.

Unified Monitoring: Organizational strategies should strive for the use of a “single pane of glass” dashboard to pull security data from all environments. Unfortunately, hybrid environments often feature fragmented monitoring and increased complexity, which create auditing challenges.

Data Residency: Audits must verify that data does not leave specific geographic locations, especially when moving between private and public clouds.

6.2 - Conduct security control testing

Security control testing can include tests of physical facilities, logical systems, and applications. Common testing methods include vulnerability assessment and scans, penetration testing, and log reviews.

Vulnerability assessments are a systematic, ongoing process for identifying, classifying, and prioritizing risks. It is a component of a larger vulnerability management program. A vulnerability scan is a high-level, automated “check-up” of the digital environment.

Vulnerability assessment

Vulnerabilities are weaknesses in systems and security controls that could be exploited by a threat. A vulnerability assessment systematically examines environments to identify, classify, and prioritize risks. Vulnerability assessments are among the most important testing tools available to a security professional.

The goal of a vulnerability assessment is to identify elements in an environment that are not adequately protected from a technical and/or physical perspective, and can include personnel, physical, facility/environment, and network testing.

Vulnerability management is a continuous, risk-based cycle of identifying, evaluating, prioritizing, and remediating security weaknesses across an organization’s entire digital landscape. It has evolved from a simple “scan-and-patch” process into an always-on discipline focused on reducing “exploitable risk” rather than just counting vulnerabilities.

Risk-Based Prioritization: Organizations should prioritize the vulnerabilities that are actually at risk of exploitation, rather than blindly following technical severity scores like CVSS.

AI Integration: AI is increasingly being used to automate triage, predict exploit likelihood, and generate on-demand remediation instructions to keep pace with sophisticated, AI-powered threats.

The goal of vulnerability management workflow is to ensure vulnerabilities are detected and resolved as quickly as possible. The process should prioritize remediation based on severity, likelihood of exploitation, and remediation difficulty. The basic steps are: detection, validation, and remediation.

NIST provides the Security Content Automation Protocol (SCAP), a common framework and suite of specifications that standardize how software flaws and security configurations are communicated to people and systems (see NIST 800-126 r3 and newly released r4).

SCAP components include:

Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE): provides a naming system for describing security vulnerabilities.

Common Vulnerability Scoring Systems (CVSS): provides a standardized scoring system for describing the severity of security vulnerabilities. It includes metrics and calculation tools for exploitability, impact, exploit code maturity, and remediation, as well as a means to score vulnerabilities against the organization’s unique requirements.

Common Configuration Enumeration (CCE): provides a naming system for system config issues.

Common Platform Enumeration (CPE): provides a naming system for operating systems, applications, and devices.

eXtensible Configuration Checklist Description Format (XCCDF): a standardized XML language used to create, document, and exchange security checklists and benchmarks, allowing compliance tools to consistently audit and harden system configurations.

Open Vulnerability and Assessment Language (OVAL): provides a language for describing security testing procedures, and is used to describe the security condition of a system.

Vulnerability scans use automated tools to probe systems, applications, and networks to identify weaknesses that attackers could exploit. Common flaws may include missing patches, misconfigurations, or faulty code.

Types of scans include:

Credentialed/Non-Credentialed scan: A credentialed scan involves providing the scanning tool with valid login details to perform a deep inspection from inside the system. A non-credentialed scan probes the system from an outside perspective, using only credentials that an attacker could easily find without special access or login rights.

Intrusive/Non-intrusive: A non-intrusive scan is a “safe” or passive scan designed to identify vulnerabilities without damaging systems or disrupting normal system operations. An intrusive or active scan can cause damage and go beyond identification by actively exploiting a vulnerability to confirm its existence and determine its potential impact.

Configuration Scans: Configuration scans or reviews typically evaluate operating systems, servers, network infrastructure, or cloud environments against industry-standard secure baselines.

There are four main categories of vulnerability scans: network discovery, network vulnerability, web application vulnerability, and database vulnerability.

Network discovery scanning methods are used to identify and map active devices and services connected to an organization’s infrastructure. They are often used to begin a vulnerability scan or penetration test, and provide the foundational visibility required for IT asset management, security monitoring, and troubleshooting. Some of the more common scanning techniques include:

TCP SYN Scanning: AKA “half-open” scanning that involves sending a single packet to each scanned port with the SYN flag set (requesting a new connection). If the response includes the SYN and ACK flags, the port is reported as open.

TCP Connect Scanning: opens a full connection to the remote system, and is used when the user doesn’t have permissions to run a half-open scan.

TCP ACK Scanning: sends a packet with the ACK flag set, with a goal of determining firewall rules and methodologies used.

UDP Scanning: checks for active UDP services on a remote system. Note that this method doesn’t use the three-way handshake, as UDP is connectionless.

Xmas Scanning: sends a packet that is “lit up” because it has so many (FIN, PSH, and URG) flags set.

NMAP is a common network discovery and scanning tool that determines the state of each port, whether open, closed, filtered (unable to be determined because the port is blocked by a firewall), or unfiltered (unblocked, but port status can’t be determined). As with many scanning tools, NMAP can also help identify specific software and versions running on network devices (a process called banner grabbing).

Network vulnerability scans: Specifically review systems and devices on the network to identify security weaknesses.

Web application vulnerability scans: used to identify flaws in software before attackers can exploit them. Methods can include SAST (static source code analysis), DAST (dynamic application security testing), and SCA (software composition analysis). Web-application scans “crawl” or “spider” a website to map all pages, links, and forms. They then simulate attacks on these entry points to identify security holes.

Database vulnerability scans: specialized security assessments designed to identify weaknesses specifically within Database Management Systems (DBMS), (e.g., SQL Server, Oracle, MySQL, PostgreSQL). Unlike general network scans that look for open ports, these scans dive into the database’s internal logic, user permissions, and configurations that protect an organization’s most sensitive data. SQLmap is a commonly used open-source database vulnerability scanner.

Penetration testing (e.g., red, blue, and/or purple team exercises)

Penetration testing is an authorized, simulated cyberattack against an organization’s IT infrastructure to identify and exploit vulnerabilities before malicious actors can. Performed by security professionals, these tests assess the resilience of networks, applications, and physical security by mimicking real-world adversary tactics. Penetration testing should be performed only by qualified professionals under contract and with explicit written permission from system owners.

Note that NIST (SP 800-15) defines the testing process as four phases (planning, discovery, attack, and reporting):

Planning: agreement on the scope of the test and the rules of the engagement.

Discovery: gathering information and doing vulnerability analysis.

Reconnaissance: Gathering intelligence about the target using passive methods (e.g., open-source intelligence or OSINT) or active probing. The goal of the reconnaissance step is to build a map of the target environment.

Enumeration: the process of gathering detailed information on target systems. This could involve:

Identifying resources, file shares, and system architecture.

Determining open ports, software versions, and banners for specific services like web servers, databases, or mail servers.

Vulnerability Analysis: the bridge between enumeration/discovery and exploitation. After the team has identified live hosts and open ports and extracted detailed system information, they need to systematically evaluate these findings to identify specific, exploitable weaknesses. This could include manual or automated vulnerability scans, and researching known vulnerabilities for specific software versions in use.

Attack: using manual and automated tools to defeat system integrity.

Exploitation: the “action” stage of a penetration test where the testers actively attempt to bypass security controls to gain unauthorized access to a system or data. While previous phases identified potential weaknesses, this phase confirms their existence by triggering the flaws. It transforms theoretical risks into proven vulnerabilities.

Successful exploitation is rarely the end of the test. It usually leads directly into Post-Exploitation, where the tester attempts to escalate their privileges, move laterally through the network, and maintain persistent access.

Reporting: considered the most critical stage of a penetration test because it transforms technical findings into a strategic roadmap for security improvement. It serves as the primary deliverable for both executive leadership to understand business risk and technical teams to implement remediation. Work product for this phase should include an executive summary, detailed findings, proof-of-concept evidence, and remediation recommendations.

Penetration tests are categorized based on the level of information and access provided to the tester. Organizations select types based on their specific threat models, such as whether they are more concerned about external hackers or malicious insiders.

Black Box Testing (zero-knowledge): This is the most realistic simulation of an external cyberattack. The tester has no prior knowledge of the target’s internal code, architecture, or credentials and must perform their own reconnaissance.

White Box Testing (full-knowledge): provides the tester with substantial or even complete information about systems and networks.

Gray Box Testing (partial-knowledge): This hybrid approach provides the tester with limited information, such as standard user login credentials or a high-level network diagram. It mimics a realistic threat from a staff member, partner, or attacker who has already established a foothold.

As part of training programs designed to help employees in their roles and to identify vulnerabilities in systems, networks, and applications, with similar results gained from penetration testing, participants are often divided into teams:

Red team: this team can include internal or external members who are on offense — attackers who attempt to gain access to systems. Their goal is to assess the organization’s systems and security controls.

Blue team: defenders who must secure systems and networks from attacks.

Purple team: bringing red and blue teams together to share information about tactics and lessons learned.

White team: observers and judges.

Log reviews

Log reviews are the systematic collection and analysis of events generated by systems, networks, and applications. They are important for daily activity monitoring, threat detection, and maintaining security and operational health. Common log capture should include data from network and security devices, applications, and change management.

Log files need to be protected by collecting and storing them securely, and using controls to restrict access. Archived logs should be set to read-only permissions to prevent modifications.

Logging systems should use the Network Time Protocol (NTP) to ensure clocks are synchronized across all systems that collect logs.

Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) systems collect log information and provide capabilities such as aggregation, normalization, secure storage, analysis, and reporting.

Synthetic transactions/benchmarks

Passive or Real User Monitoring (RUM) observes and captures data from actual users as they interact with a website. It’s called “passive” because the monitoring tool does not generate traffic; it simply listens to a user session. This type of monitoring is good for performance monitoring and identifying specific issues a user is experiencing. Things to keep in mind when using RUM:

Issues will only be observed after a user has experienced them.

Because real user data is collected, data privacy needs to be addressed.

Active monitoring uses automated scripts to simulate user behavior in a controlled, predictable environment. It uses synthetic or simulated user interactions or transactions to test system functions and performance (e.g., a website’s capacity to handle high traffic). Synthetic transactions can be used to proactively test new features in staging or dev environments before releasing them to users, and to establish a “clean” performance baseline free of the noise from varied user devices.

Code review and testing

Code review and testing are the most critical components of a software testing program. These procedures provide third-party reviews of developers' work before moving code into production. Code reviews help discover security, performance, or reliability flaws in applications before they go live and negatively impact business operations.

In code review, developers other than the one who wrote the code review it for defects. Code review can be a formal or informal validation process.

Note that a Fagan inspection is a formal code review process that follows six steps:

Planning: The moderator selects the inspection team, identifies the materials to be reviewed, and schedules the necessary meetings.

Overview: The author provides a brief group presentation to educate the inspection team on the work product’s purpose and background.

Preparation: Each team member individually reviews the work product in detail to identify potential defects prior to the group meeting.

Inspection: The team meets to systematically review the product; a “reader” paraphrases the content while “inspectors” point out and log defects for later correction (problem-solving is avoided in this stage).

Rework: The author corrects all identified defects in the work product.

Follow-up: The moderator verifies that every logged defect has been properly fixed and that no new errors were introduced during the rework.

Entry criteria are the requirements that must be met to start a specific process, and exit criteria are the requirements that must be met to complete it. Entry and exit criteria function as “quality gates,” ensuring that testing phases begin only when prerequisites are met and conclude only when quality goals are achieved.

In the context of security testing, these criteria ensure that Static Application Security Testing (SAST) and Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST) are integrated effectively into the CI/CD pipeline.

Static Application Security Testing (SAST): evaluates the security of software without running it by analyzing either the source code or the compiled application. Code reviews are an example of static app security testing.

Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST): evaluates the security of software in a runtime environment and is often the only option for organizations deploying applications written by someone else.

Misuse case testing

Robust software quality and intended system operations and security are achieved by examining a system through two opposing lenses: use case testing, which validates desired functionality, and misuse case testing, which proactively identifies potential threats.

Misuse case testing (often called abuse case testing) is the inverse of a use case. It models “upside down” scenarios to identify what the system should not allow.

While use case testing ensures a product is usable, misuse case testing ensures it is resilient. This has become critical for several reasons:

Prevents business logic vulnerabilities: Standard automated scans often miss logic errors (e.g., manipulating a URL to see another user’s private data). Misuse cases specifically target these multi-step, logic-based attacks.

Reduces “time-to-exploit” risk: Attackers use AI to discover and exploit vulnerabilities faster than ever. Designing against misuse cases allows developers to build defenses during the coding process rather than patching after a breach.

Addresses AI-orchestrated threats: Misuse cases are essential for modeling how these new threat actors might manipulate AI model inputs or memory to cause harm.

Compliance & audit readiness: Regulations like PCI DSS and GDPR require organizations to demonstrate that they have accounted for both accidental misuse (e.g., input errors) and intentional abuse (e.g., data theft).

Coverage analysis

A test coverage analysis measures how well testing has covered security use cases, such as controls and attack vectors.

Test coverage is simply the number of use cases tested divided by the total number of use cases.

Five common criteria used for code test coverage analysis:

Branch coverage: Have all IF statements been executed under all IF and ELSE conditions?

Condition coverage: Have all logical tests in the code been executed under all sets of inputs?

Functional coverage: has every function in the code been called and returned results?

Loop coverage: has every loop in the code been executed under conditions that test associated code execution (e.g., multiple times, only once, or not at all)?

Statement coverage: has every line of code been executed during the test?

Test coverage report: measures how many of the test cases have been completed, and is used to provide test metrics when using test cases.

Interface testing (e.g., user interface, network interface, application programming interface (API))

Interface testing is the validation of the communication and data exchange between different systems, modules, or layers of an application. It ensures that integrated individual components don’t fail even if they work perfectly in isolation.

1. User Interface (UI) Testing

UI testing evaluates the visual and interactive elements that end users directly engage with.

Focus: How users interact with an application. Ensuring that elements such as forms, fonts, input, and layouts function correctly and maintain visual consistency.

Goal: Ensuring a seamless experience across thousands of devices and browser combinations, with a growing emphasis on accessibility and AI-driven visual regression.

2. API Testing

API testing validates communication between software or system components by verifying the logic, testing different inputs, ensuring expected outputs, and validating error handling.

Focus: Examines endpoints for performance, security (e.g., SQL injection), and reliability without using a graphical interface.

Goal: Faster, more stable, and more secure integration between application components.

3. Network Interface Testing

Network interface testing focuses on how different entities communicate over a network, especially during connection resets or outages.

Focus: Verifies data transmission, network protocols, and connectivity, and that a solution can handle failures in the link between an application server and a website or third-party service. It may also be used to ensure that sensitive data is accessible only to authorized network users.

Goal: High-priority for cloud and hybrid environments to ensure data is transferred securely and completed without packet loss and high latency.

4. Physical Interface Testing

Used for applications that integrate with machinery or hardware components, this type of testing validates the connection between physical components or multi-level systems.

Focus: Includes testing hardware-to-software connections (like barcode scanners to inventory apps) and ensuring environmental systems (for instance, power and cooling) interact safely with data center hardware.

Goal: Ensures correct data transfer and integration between components with physical connections, and is essential for specialized or legacy hardware that cannot be easily emulated in the cloud.

Breach attack simulations

Breach and Attack Simulation (BAS) is an automated cybersecurity platform that continuously tests an organization’s security posture by emulating real-world attack techniques and tactics. Unlike manual penetration testing or periodic red teaming, BAS can provide an “always-on” validation process to identify vulnerabilities before adversaries can exploit them.

These platforms can help assess the organization’s ability to detect, respond to, and remediate an attack. With integrated AI and machine learning, they can generate more unpredictable scenarios and align dynamic simulations with real-time threat intelligence feeds. Many organizations also use BAS to benchmark their Security Operations Center (SOC) performance, measuring how quickly it can detect and respond to simulated alerts.

Compliance checks

Compliance checks are systematic reviews and technical tests designed to verify that an organization’s systems, processes, and personnel comply with specific legal, regulatory, and industry standards (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA, SOC 2, or NIST).

These checks serve as an ongoing “safety net,” catching issues early to avoid legal penalties, data breaches, and reputational damage.

Compliance checks involve a blend of administrative reviews and automated technical validations, such as:

Documentation Review: Periodically examining internal governance libraries, such as security policies, incident response plans, and network diagrams, to ensure they are current and accessible.

Continuous Monitoring: Implementing automated tools to watch for “configuration drift,” new vulnerabilities, and deviations from security baselines in real-time.

Training & Awareness Evaluation: Assessing employee comprehension of compliance responsibilities, and provide on-going and validation training.

Record-Keeping & Evidence Collection: Maintaining retrievable artifacts (e.g., logs and training records) to serve as a “defensible trail” during external audits.

Organizations are moving away from “checkbox” compliance toward a real-time, ongoing model, often called Continuous Compliance Automation (CCA), that requires a shift from reactive auditing to proactive, data-driven governance. This transition enables organizations to be “audit-ready” every day rather than just during a specific audit season.