Understanding CISSP Domain 4: Communication and Network Security - Part 1

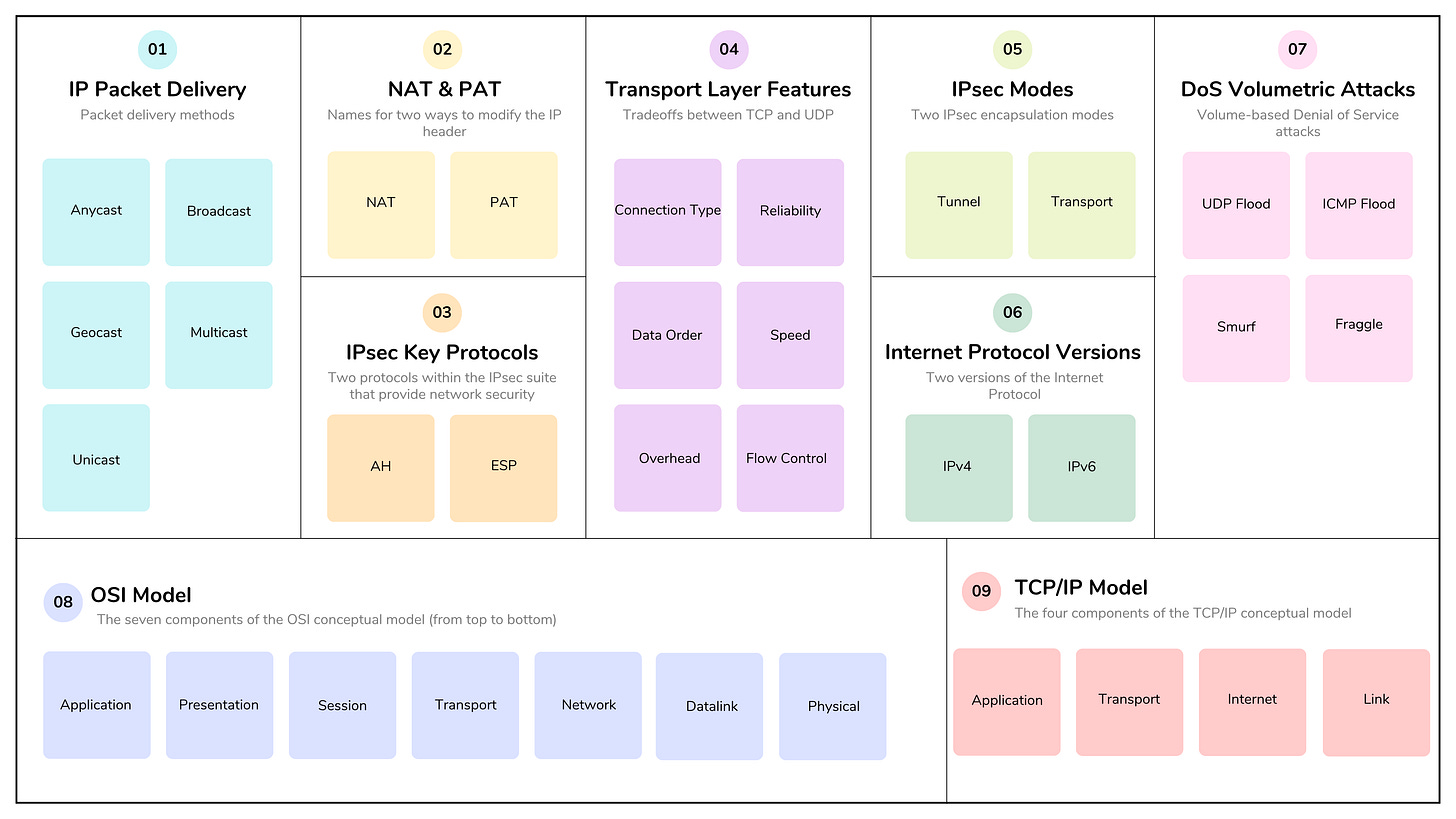

Communication and Network Security covers the design and protection of enterprise network architecture, secure communication channels, and the technologies used to move and protect data across those networks. Representing 13% of the CISSP exam, this domain is more technical than others, but it also emphasizes applying security principles to network design and operation at a strategic level. Candidates are expected to understand and apply concepts such as layered network models (e.g., OSI and TCP/IP), secure protocols, network topologies, and wireless security.

Let’s dive into the domain and cover the material by following the ISC2 exam outline.

4.1 Apply secure design principles in network architectures

Applying secure design principles in network architectures means integrating fundamental security concepts and best practices from the very beginning of the network design lifecycle to create systems that are inherently resilient to attacks and minimize vulnerabilities. Security is a core design constraint, not an afterthought.

Open System Interconnection (OSI) and Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) models

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model and the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) model are both conceptual frameworks that use a layered approach to describe how devices communicate over a network.

The OSI model is a generic, protocol-independent standard that divides network communication into seven distinct layers to promote interoperability between different vendor products. Each layer performs specific, self-contained functions.

Communication between layers is via encapsulation (at each layer, the previous layer’s header and payload become the current layer's payload), and de-encapsulation provides the inverse action as data moves up the stack.

Layer 7: Application - The interface between user applications (e.g., web browsers, email clients) and the network, providing services like file transfer and email.

Layer 6: Presentation - Handles data format translation, compression, and encryption/decryption, ensuring data is in a usable format for the Application layer.

Layer 5: Session - Manages and controls connections (sessions) between applications, including establishing, coordinating, and terminating communication.

Layer 4: Transport - Provides reliable end-to-end data delivery by segmenting data, managing flow control, and ensuring error recovery using protocols like TCP and UDP.

Layer 3: Network - Determines the best path (routing) for data packets across different networks using logical addressing and path determination, and handles traffic control and packet sequencing.

Layer 2: Data Link - Manages node-to-node data transfer within the same local network, handling physical addressing (MAC addresses), framing, and basic error detection.

Layer 1: Physical - Deals with the physical connectivity and transmission of raw data bits as electrical signals, light pulses, or radio waves over a medium (cables, Wi-Fi).

The Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) model (also known as the DARPA or DOD model) has four layers:

Application (AKA Process)

Transport (AKA Host-to-Host)

Internet (AKA Internetworking)

Link (AKA Network Interface or Network Access)

A Protocol Data Unit (PDU) is a single unit of information that is transmitted between network devices at a specific layer of the OSI or TCP/IP networking models.

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) and UDP (User Datagram Protocol) are both transport layer protocols, but they offer a trade-off between reliability and speed. TCP is a connection-oriented, reliable protocol with guaranteed delivery, while UDP is a connectionless, faster protocol that does not guarantee delivery or order.

Use TCP/IP when reliability, order, and data integrity are critical (i.e. the application cannot tolerate missing or corrupted data).

Use UDP when speed and low latency are more important than perfect reliability, and the application can tolerate some data loss.

The three-way handshake is the foundational process used by TCP to establish a reliable, connection-oriented session between two devices (a client and a server) before any actual data is transmitted.

It is a crucial mechanism that ensures both sides are ready, reachable, and synchronized to begin a stable communication session. Steps in the three-way handshake follow in the table below.

MAC and ARP

A Media Access Control (MAC) address is a unique, physical hardware address assigned to a network interface card (NIC) by its manufacturer. A MAC address is used for device identification and data delivery at the Data Link layer (Layer 2) of the OSI model within a local network. It is a 48-bit (6-byte) address, represented as 12 hexadecimal digits (e.g., 00:1B:63:84:45:E6). MAC addresses are generally fixed and permanent, and embedded in the hardware, unlike IP addresses which are assigned dynamically and can change.

Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) is a communication protocol used to discover and map IP address to MAC addresses on the same local network. It bridges the gap between the logical IP address (Layer 3) that applications use and the physical MAC address (Layer 2) needed for actual data transmission on a local link.

ARP and MAC-related Attacks

ARP Spoofing/Poisoning: This is the most common ARP attack. An attacker sends falsified ARP messages to a target device (like a computer or router), linking the attacker’s MAC address with the IP address of a legitimate network device.

ARP Flooding (ARP Cache Overflow): An attacker floods the network with excessive ARP requests or replies using random MAC and IP addresses consuming resources and causing legitimate entries to be pushed out of the ARP tables and potentially leading to a DoS condition.

MAC Spoofing: An attacker changes their device’s hardware MAC address to match that of an authorized, legitimate device already on the network, allowing the attacker to bypass access control measures like MAC filtering or port security.

MAC Flooding (CAM Table Overflow): An attacker sends a large number of Ethernet frames with unique, fake source MAC addresses to a network switch, overwhelming the switch’s Content Addressable Memory (CAM) table. A CAM table is used to map MAC addresses to physical ports. When the table is full, the switch enters “fail-open mode” and begins broadcasting all incoming traffic to all ports (acting like an old-fashioned hub), allowing the attacker to capture and analyze all traffic using a packet sniffer.

ARP and MAC Attack Countermeasures

For critical devices like default gateways or servers, administrators can manually configure static (permanent) entries in the ARP cache on all workstations and network devices.

Dividing the network into smaller, isolated Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs) limits the broadcast domain of ARP messages, containing the impact of any potential ARP poisoning attack to a smaller group of devices.

While using encryption doesn’t stop the attacks themselves, encrypting data during transmission ensures that even if an attacker successfully intercepts traffic via a On-Path (MiTM) attack, the data remains unreadable.

Using network monitoring tools and Intrusion Detection/Prevention Systems (IDS/IPS) can help detect unusual ARP activity or MAC address changes and alert administrators to an attack in progress.

Domain Name System (DNS)

The Domain Name System (DNS) translates human-readable domain names (e.g., www.example.com) into an IP addresses (e.g., 192.0.2.1) that computers use to locate and communicate with each other. DNS was initially designed for speed and usability rather than security, which created several inherent vulnerabilities. By default, DNS queries and responses are sent in plaintext (via UDP), which means they can be read by ISPs, or anybody able to monitor transmissions. Even if a website uses HTTPS, the DNS query required to navigate to that website is exposed.

DNS Attacks

DNS Spoofing / Cache Poisoning: The most common attack, where an attacker injects false DNS data into a DNS resolver’s cache. This causes the server to return an incorrect IP address for a legitimate domain, redirecting users to a malicious website (often a phishing site) without their knowledge.

DNS Hijacking: An attacker gains unauthorized control over a domain’s DNS settings (usually by compromising a domain registrar account or home router) and changes the authoritative DNS records to point to a malicious server.

Denial of Service (DoS/DDoS) Attacks: Attackers flood DNS servers with an overwhelming number of legitimate or non-existent domain requests consuming server resources and preventing legitimate users from accessing services or websites.

DNS Attack Countermeasures

Implement DNS Security Extensions (DNSSEC): DNSSEC uses digital signatures and public-key cryptography to authenticate DNS data, confirming the data originated from the correct source and hasn’t been tampered with. This is the primary defense against DNS spoofing and cache poisoning.

Encrypt DNS Traffic: Use protocols such as DNS over HTTPS (DoH) or DNS over TLS (DoT) to encrypt DNS queries between clients and recursive resolvers. This prevents On-Path (MiTM) attacks and eavesdropping.

Protocols and Ports

While the exam focuses on a deep understanding of security concepts over rote memorization, familiarity with common network ports and their associated protocols is crucial for a security professional.

Here is a list of essential ports, their functions, and key security considerations relevant to the CISSP exam.

Internet Protocol (IP) version 4 and 6 (IPv6) (e.g., unicast, broadcast, multicast, anycast)

IPv4 and IPv6 are the two primary versions of the Internet Protocol (IP). IP provides unique identifiers for devices and routes data across the internet. The primary distinction between the versions lies in their address space, with IPv6 being developed to solve the critical problem of IPv4 address exhaustion and provide other enhancements for modern networking.

IPv4 Overview

Address Format: Uses 32-bit numeric addresses written in a dotted-decimal format (e.g., 192.0.2.0).

Address Space: Offers approximately 4.3 billion unique IP addresses.

The IPv4 private address space, defined by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) in RFC 1918, consists of three specific address blocks that are reserved for use within private networks and are not publicly routable on the global internet.

Key Features: IPv4 has a variable header size (20-60 bytes), uses a checksum for error detection, and relies on protocols like Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) for address assignment and Network Address Translation (NAT) to extend its lifespan.

Limitations: The limited address space led to address scarcity with the explosion of internet-connected devices, necessitating complex workarounds like NAT, which can add latency and management issues.

IPv6 Overview

Address Format: Uses 128-bit alphanumeric addresses, written as eight groups of four hexadecimal digits separated by colons (e.g., 2001:0db8:85a3::8a2e:0370:7334).

Address Space: Provides a virtually inexhaustible number of addresses (approximately 340 undecillion, or 3.4×10^38).

Key Features: Features a fixed, simplified header (40 bytes) for more efficient routing and faster processing, built-in Quality of Service (QoS) support, and stateless address autoconfiguration (SLAAC). It mandates built-in security features through IPSec, which is optional in IPv4.

Advantages: Eliminates the need for NAT, restoring end-to-end connectivity, and is better suited for emerging technologies like IoT and 5G networks.

Delivery methods of IP packets

Anycast (One-to-any nearest): A single sender transmits data to the nearest or best-suited node in a group of potential recipients (e.g., Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) use anycast to direct users to the nearest server).

Broadcast (One-to-all): A single sender transmits data to all possible recipients within the same local network segment (broadcast domain). Routers typically do not forward broadcast traffic to other networks to prevent network congestion.

Geocast (One-to-geographic area): A specialized method, primarily used in wireless ad-hoc and sensor networks, where data is delivered to all nodes within a specific geographic region rather than a specific IP address or group membership.

Multicast (One-to-many): A single sender transmits data to a specific group of interested recipients that have explicitly requested to join the multicast group (e.g., streaming video, online gaming).

Unicast (One-to-one): A single sender transmits data to a single, unique recipient identified by a specific IP address.

Network Address Translation (NAT) is a general term for any technology that modifies the IP addresses in the header of a packet as it passes through a routing device. Port Address Translation (PAT), also known as NAT Overload, is a specific form of NAT that also translates both the IP address and the port number.

NAT primarily translates private, non-routable IP addresses (like those in the 10.0.0.0/8 range) used within a local network into publicly routable IP addresses used on the internet. NAT translates IP addresses without changing port information, via one-to-one (static NAT) or many-to-one (dynamic NAT). NAT protects the addressing scheme of a private network, allowing the use of private IP addresses, and enables multiple internal clients to obtain internet access through a few public IP addresses.

PAT is an extension of NAT that was developed to address the IPv4 address shortage more efficiently. It allows multiple private IP addresses to share a single public IP address by changing and tracking both the IP address and the source port number of outgoing packets for each connection.

Network attacks

Denial-of-Service (DoS) and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks aim to make a network, service, or application unavailable to legitimate users by overwhelming it with traffic or resource requests.

A DoS attack originates from a single source (one computer/connection) targeting a specific system, with the goal of consuming its resources (bandwidth, memory, CPU) or exploiting a software vulnerability to cause it to slow down or crash.

Effective Countermeasures:

IP-based Access Control Lists (ACLs): Since the attack comes from a single IP, a simple and effective measure is to configure firewalls or routers to block all traffic from the specific malicious source IP address.

Rate Limiting: Limiting the number of requests a server can accept within a specific time frame can help manage traffic spikes and prevent resource exhaustion, though it may not be sufficient for more complex attacks.

Intrusion Prevention Systems (IPS): These systems monitor network traffic for suspicious patterns and can be configured to alert administrators or automatically block known attack signatures.

A DDoS attack is a more potent and complex form of DoS. It leverages multiple compromised devices (forming a “botnet”) to flood a target from various locations simultaneously. This distributed nature makes it significantly harder to detect and mitigate, as the malicious traffic is harder to distinguish from legitimate user traffic.

Effective Countermeasures:

DDoS Mitigation Services: The most effective defense is a cloud-based DDoS protection service (often provided by third parties like Cloudflare, Akamai, or AWS Shield) that can absorb and filter massive volumes of malicious traffic before it reaches the target network.

Traffic Monitoring and Analysis: Proactive monitoring of network traffic to establish a “normal” baseline is vital. Unusual spikes from a single IP range, odd geographic sources, or unnatural patterns can indicate an ongoing attack and trigger countermeasures.

Web Application Firewalls (WAFs): WAFs are helpful for defending against application-layer DDoS attacks. They can be configured to filter HTTP/HTTPS requests based on a set of rules to block malicious traffic that mimics legitimate user behavior.

Specific types of DoS attacks can be broadly categorized into volumetric attacks, protocol attacks, and application-layer attacks, based on which part of the network stack they target.

Volumetric Attacks (Layer 3 & 4)

UDP Flood: The attacker sends a large number of User Datagram Protocol (UDP) packets to random ports on the target. The target system then attempts to respond with an ICMP “Destination Unreachable” packet, which depletes its resources.

ICMP Flood (Ping Flood): The attacker overwhelms the target with ICMP Echo Request packets (pings) faster than the target can respond, saturating the incoming bandwidth.

Smurf Attack: An attacker sends an ICMP ping request to a network’s broadcast address with a spoofed source IP of the victim. All devices on that network respond to the victim, flooding it with traffic.

Fraggle Attack: A type of Denial-of-Service (DoS) and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) amplification attack that is a variation of the Smurf attack. The key difference is that while a Smurf attack uses ICMP (Internet Control Message Protocol) packets, a Fraggle attack uses spoofed UDP (User Datagram Protocol) packets to achieve its objective.

Protocol Attacks (Layer 3 & 4)

SYN Flood: This attack exploits the TCP three-way handshake process. The attacker sends a rapid sequence of SYN requests but never sends the final ACK packet. The target server leaves connections half-open, quickly exhausting its capacity to handle new, legitimate connections.

Teardrop attack: A type of Denial-of-Service (DoS) attack that exploits a vulnerability in the way older or unpatched operating systems reassemble fragmented IP data packets by sending fragmented packets to the target.

Ping of Death: An older attack where the attacker sends a malformed (oversized or fragmented) ICMP packet to the target. When the target tries to reassemble the packet, it causes the system to crash.

Land attack: A specific type of Denial-of-Service (DoS) attack where the attacker sends a specially crafted network packet to a target machine with a forged header in which the source IP address and port are the same as the destination IP address and port of the target system.

Application-Layer Attacks (Layer 7)

HTTP Flood: The attacker sends a high volume of seemingly legitimate HTTP GET or POST requests to a web server. This forces the server to use excessive resources to respond to each request, making the service slow or unavailable.

DNS Query Flood: The attacker floods a specific DNS server with a high volume of malicious DNS queries, consuming resources and preventing it from responding to legitimate requests.

DDos attacks are often carried out via bots and botnets. Bots are the compromised individual computers, a botnet is the network of these devices, and the bot herder is the cybercriminal who controls them. Bot herders use a command-and-control (C&C) infrastructure to send instructions to the bots, often anonymously through various communication channels. Bot herders may use the botnet for their own attacks or rent access to it to other criminals on the dark web for a fee.

Countermeasures for bots include keeping systems patched, and using a defense in depth strategy to protect endpoints.

Eavesdropping is the unauthorized, covert interception of private communications between two or more parties. In the context of networks, the goal of an eavesdropping attack (also known as a sniffing or snooping attack) is to steal sensitive information such as login credentials, financial data, or trade secrets, without the knowledge of the communicating parties.

Impersonation, in the context of network attacks, is where an attacker successfully pretends to be a legitimate user, entity, or system to gain unauthorized access to data, systems, or services. The goal is to trick other network components, users, or applications into believing the attacker is a trusted participant. Common techniques include IP and MAC address and DNS spoofing, Session Hijacking, and On-Path (MitM) attacks.

Eavesdropping attacks primarily exploit vulnerabilities in unsecured network communications.

Packet Sniffing: Attackers use packet sniffers tools (like Wireshark) to capture and analyze data packets as they travel across a network.

Unencrypted Networks: When data is transmitted without encryption (e.g., over an unsecured public Wi-Fi hotspot or an HTTP website), an attacker can easily read the contents of the intercepted packets.

On-Path (AKA MiTM) attacks: In a more active form of eavesdropping, the attacker positions themselves between the two communicating parties, secretly intercepting and relaying messages. This allows them not only to listen but also to potentially alter the data being exchanged.

The primary defense against eavesdropping is the use of strong encryption via VPN to secure communication channels, and HTTPS to secure web browsing.

A replay attack (also known as a playback attack) is a form of network attack in which an attacker covertly intercepts and retransmits valid data transmission or sequence of data transmissions to fraudulently repeat an effect or gain unauthorized access. The core vulnerability in a replay attack lies in the system’s inability to distinguish between the original, legitimate transmission and the subsequent, malicious retransmission of the exact same data.

The primary defense against replay attacks is to ensure that a captured message cannot be reused. This is typically achieved by using nonces (a unique random value), timestamps, session IDs and sequence numbers, and strong encryption.

Secure protocols (e.g., Internet Protocol Security (IPSec), Secure Shell (SSH), Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)/ Transport Layer Security (TLS))

Secure protocols use encryption, authentication, and integrity checks to protect data in transit from eavesdropping and tampering. The primary protocols, IPsec, SSH, and SSL/TLS, operate at different layers of the network stack and serve distinct purposes.

Internet Protocol Security (IPSec): IPsec is a suite of protocols that provides security services at the Network (Layer 3) layer, making it transparent to most applications. IPsec helps keep data sent over public networks secure. It is often used to set up VPNs, and it works by encrypting IP packets, and authenticating the packet source.

Secure Shell (SSH): a cryptographic network protocol for operating services securely over an unsecured network at the Application (Layer 7) layer. It provides a secure way for remote login to servers, primarily used by network administrators and developers for secure remote administration of servers and network devices.

Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)/Transport Layer Security(TLS): SSL and its successor, TLS, are cryptographic protocols that secure communication between applications over the internet, operating primarily at the Transport (Layer 4) layer. Commonly used for secure web browsing (HTTPS), and protecting sensitive user data (login credentials, credit card details). When you connect to a secure website, TLS uses X.509 certificates to verify the server’s identity and encrypt the communication channel between the client and server.

Authentication Protocols

Authentication protocols are mechanisms used to verify the identity of a user or device before granting access to network resources. They evolved from simple, insecure methods to more robust and encrypted systems designed for modern security requirements.

PPP (Point-to-Point Protocol): a data link layer successor to Serial Line Internet Protocol (SLIP) that provides a standard way to encapsulate network traffic over point-to-point links. It supports CHAP, PAP, and EAP.

PAP (Password Authentication Protocol): a simple, older authentication protocol defined within the PPP framework. PAP transmits usernames and passwords in clear text, making it insecure.

CHAP (Challenge-Handshake Authentication Protocol): CHAP is a significant improvement over PAP, offering much greater security for authenticating over PPP links. It uses a challenge-response mechanism and a hashed (encrypted) shared secret (password). The password is never sent in plaintext over the network. Note that MS-CHAP is the Microsoft implementation of the protocol.

EAP (Extensible Authentication Protocol): EAP is an authentication framework rather than a single protocol. It supports multiple authentication methods and is the fundamental protocol used in modern wireless networks (WPA-Enterprise) and point-to-point connections.

Some EAP derivatives include the following:

Lightweight Extensible Authentication Protocol (LEAP): a proprietary wireless LAN authentication method developed by Cisco to address initial security limitations in early Wi-Fi standards. LEAP is now considered an outdated and insecure protocol.

Protected EAP (PEAP): one of the most common methods that operates within the EAP framework. Developed to address a security flaw, PEAP creates an encrypted TLS tunnel between the client and the authentication server before any credentials are exchanged. Developed by Microsoft, Cisco, and RSA Security as an alternative to EAP-TTLS.

Extensible Authentication Protocol-Subscriber Identity Module (EAP-SIM) is an EAP method used for authentication and session key distribution in wireless networks (like Wi-Fi) by leveraging the credentials stored on a user’s GSM (Global System for Mobile communications) SIM card.

Extensible Authentication Protocol-Flexible Authentication via Secure Tunneling (EAP-FAST) is an EAP method developed by Cisco as a secure replacement for the older, vulnerable LEAP protocol.

Extensible Authentication Protocol-Message Digest 5 (EAP-MD5) is one of the simplest and original methods used within the EAP framework for user authentication. It hashes passwords with MD5, is considered highly insecure, and should be avoided.

Extensible Authentication Protocol-Protected One-Time Password Protocol (EAP-POTP) is an EAP method specifically designed to securely handle authentication using One-Time Password (OTP) tokens in multi-factor authentication, as defined in RFC 4793.

Extensible Authentication Protocol-Transport Layer Security (EAP-TLS) is considered the gold standard for enterprise-grade network authentication, based on an open IETF standard. It uses TLS for protecting authentication traffic.

Extensible Authentication Protocol-Tunneled Transport Layer Security (EAP-TTLS) an extension of EAP-TLS that provides a secure, flexible way to authenticate network users without the complexity of managing client-side digital certificates.

EAP Internet Key Exchange v2 (EAP-IKEv2) is an authentication method (defined in RFC 5106) based on the IPsec Internet Key Exchange version 2 (IKEv2) protocol. It supports authentication using passwords, symmetric keys, or asymmetric key pairs providing mutual authentication, session key establishment.

Extensible Authentication Protocol-Nimble Out-of-Band Authentication (EAP-NOOB) is a specialized EAP method designed to bootstrap things like IoT devices that lack any pre-configured authentication credentials. It uses channels such as QR codes, NFC tags and audio.

IEEE 802.1X is a “port-based access control” standard that provides encapsulated EAP authentication framework for devices trying to connect to a network. “Port-based” simply means that it works with any type of any network link (e.g. switch port or wireless access point). Remember that 802.1X isn’t a wireless technology per se, it’s an authentication technology that can be used for any type of device requiring authentication (e.g. firewalls, routers, proxies, VPN gateways etc.).

VPN Protocols

Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP) is an older obsolete protocol that encapsulates data to be sent across an IP network. The initial tunnel negotiation process is not encrypted, and thus usernames and hashed passwords could be intercepted.

Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol (L2TP) defines how data packets are encapsulated and transported across a network. L2TP does not provide encryption or strong authentication on its own, it only creates the “tunnel” through which data travels. To provide a secure VPN connection with confidentiality and integrity, L2TP uses IPsec. In other words, L2TP/IPsec provides confidentiality, integrity, and authentication of tunneled data.

Internet Protocol Security (IPSec) is the de facto standard for building VPNs because it creates secure, encrypted tunnels between devices or entire networks.

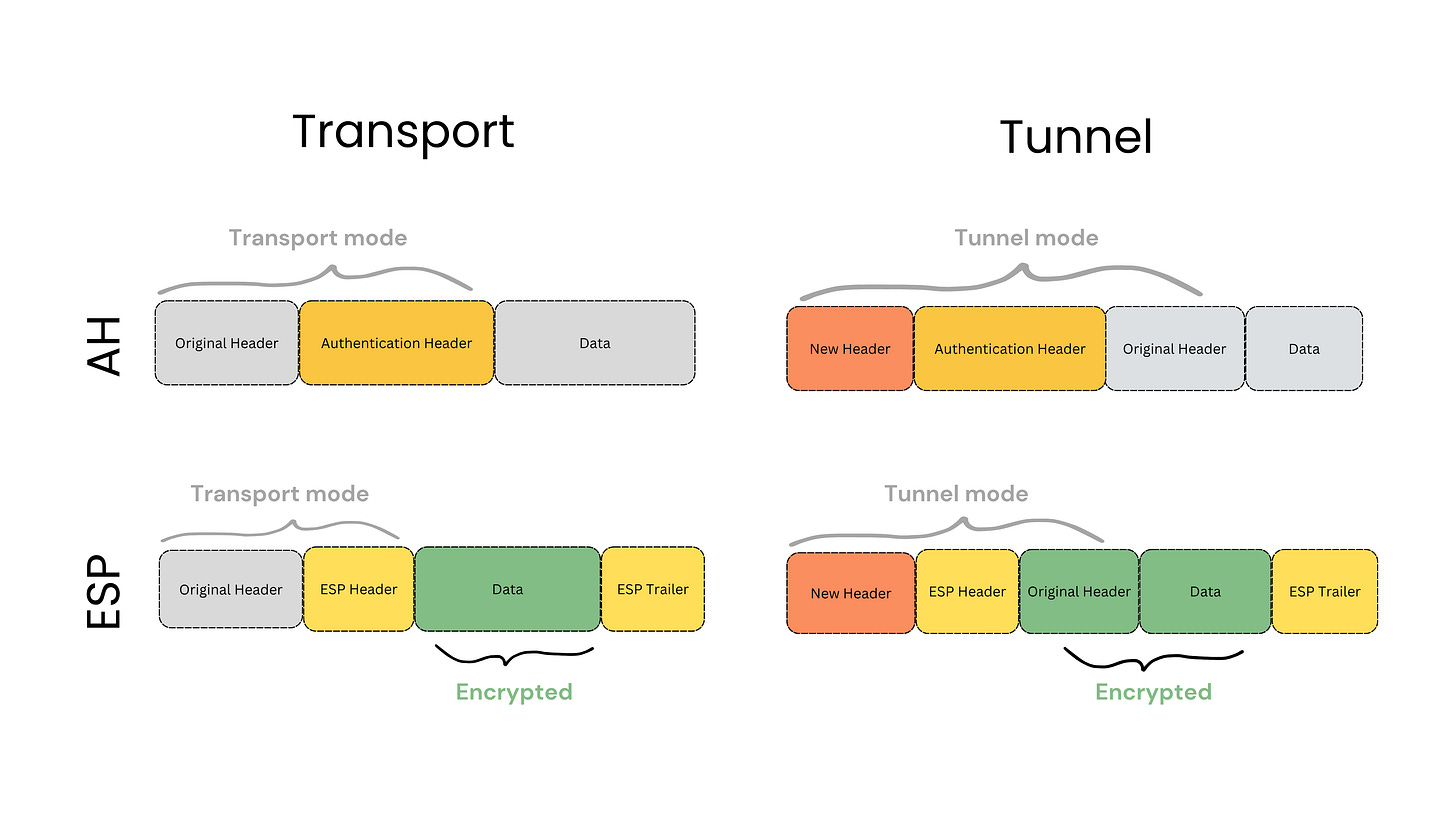

IPSec Key Protocols

Authentication Header (AH) provides data integrity and nonrepudiation, and primary authentication for IPsec. AH implements session access control and prevents replay attacks, but does not encrypt the data. For this reason, ESP is typically preferred for most modern VPN implementations where privacy is required.

Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP) is the most common protocol used in VPNs. ESP provides encryption, and prevents replay attacks. ESP provides confidentiality, integrity, and limited authentication. It is often used with AH to provide both privacy and authenticity of transmitted data.

IPSec Modes of Operation

Tunnel Mode: In this mode the entire original IP packet is encapsulated within a new IP header that routes it to the VPN gateway. This mode is used for site-to-site VPNs where entire networks communicate securely over an untrusted network (like the internet).

Transport Mode: In this mode, only the data payload of the original packet is encrypted, leaving the original IP headers intact. This mode is typically used for host-to-host communication or client-to-site VPNs. Transport mode can use a split tunnel, where only client traffic destined for the private network goes through the VPN tunnel, or full tunnel, where all client traffic is sent through the VPN.

In part two, we’ll continue through Domain 4, and objectives 4.1 forward. If you’re on the CISSP learning journey, keep studying and connecting the dots, and let me know if you have any questions about this domain.