Understanding CISSP Domain 7, Security Operations - Part 1

Security operations is the practical application of security concepts to identify, investigate, and mitigate risks throughout a business's daily activities and operational lifecycle. Comprising 13% of the exam, the domain covers areas like investigation and digital forensics, incident management, resource protection, and configuration and patch management.

The goal is to minimize the impact of threats while ensuring the organization meets its confidentiality, integrity, and availability objectives during normal, emergency, and recovery operations.

In Part 1, we’ll cover objectives 7.1 through 7.4. Let’s dive into the domain and cover the material by continuing to follow the ISC2 exam outline.

An investigation is simply the way we dig into what happened during a security incident to figure out how it started.

Security incidents can be anything from minor issues that don’t need follow-up to serious situations that require a formal investigation. A more serious incident investigation might involve law enforcement. Important investigations should follow a more formal process to avoid issues that might weaken or derail a case.

The following are some general high-level components of a formal investigation:

Identify and secure the scene

Protect evidence to preserve its integrity and the chain of custody

Identify and examine the evidence

Do an analysis of the most compelling evidence

Provide a final report of findings

Note that we covered different types of investigations in Domain 1, but to briefly review:

Administrative: cover operational issues or violations of an organization’s policies.

Criminal: is centered around court admissibility and is conducted by law enforcement.

Civil: conducted by lawyers or private investigators to gather evidence, establish liability, and determine damage or liability amounts.

Regulator: conducted by a regulatory body against an organization suspected of an infraction.

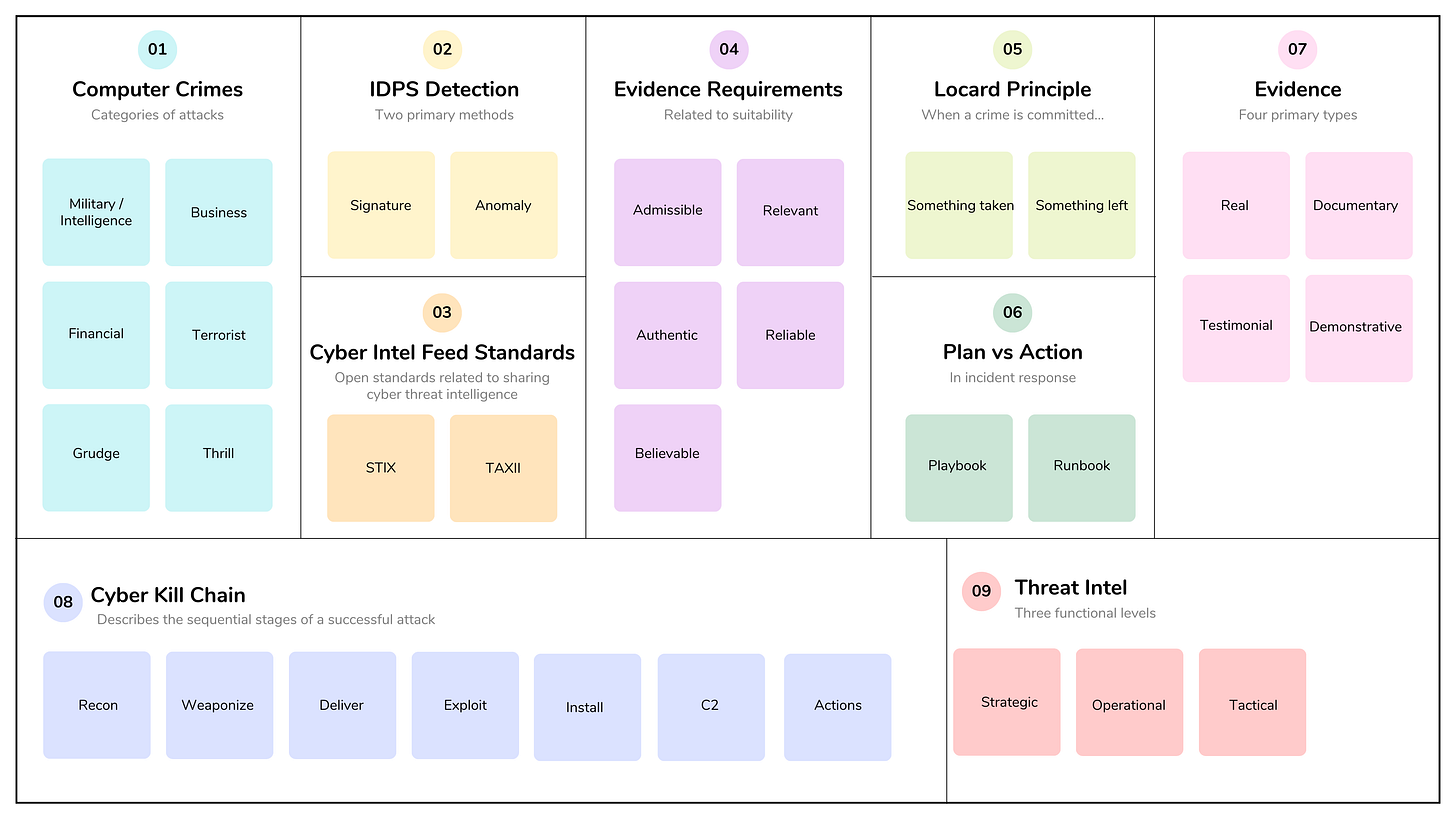

Computer crime is a law or regulation violation that involves a computing device and can be grouped into six categories:

Military and Intelligence Attack: Often carried out by foreign intelligence agents, state-sponsored actors, or traitors looking for classified military or law enforcement information. The goal is often cyber espionage (stealing proprietary data for political or strategic advantage) or cyber sabotage to disrupt an adversary’s critical infrastructure or military readiness.

Business Attack: Targets a company to gather intelligence (stealing trade secrets or intellectual property) and DOS attacks intended to disrupt a competitor’s operations or damage their reputation.

Financial Attack: Attacks targeting financial institutions, e-commerce sites, etc., to steal or embezzle funds. Tactics include stealing credit card numbers, committing identity theft, or using phishing to gain unauthorized access to online financial accounts.

Terrorist Attack: Ideologically motivated attacks designed to incite fear or cause violence against civilian targets. Used to recruit members, spread fear, and cause disruption. Terrorists may target critical infrastructure, such as power grids or communication systems, to cause widespread social or economic disruption.

Grudge Attack: These are personal attacks motivated by revenge, typically carried out by a disgruntled employee or former affiliate. The attacker seeks to damage the organization by deleting critical data, planting logic bombs, or leaking sensitive data.

Thrill Attack: Often categorized as amusement or curiosity attacks, by thrill-seekers or "script kiddies" for the excitement of successfully breaching a system. While the attackers may not intend to cause severe harm, their unauthorized access remains illegal and can inadvertently lead to system instability.

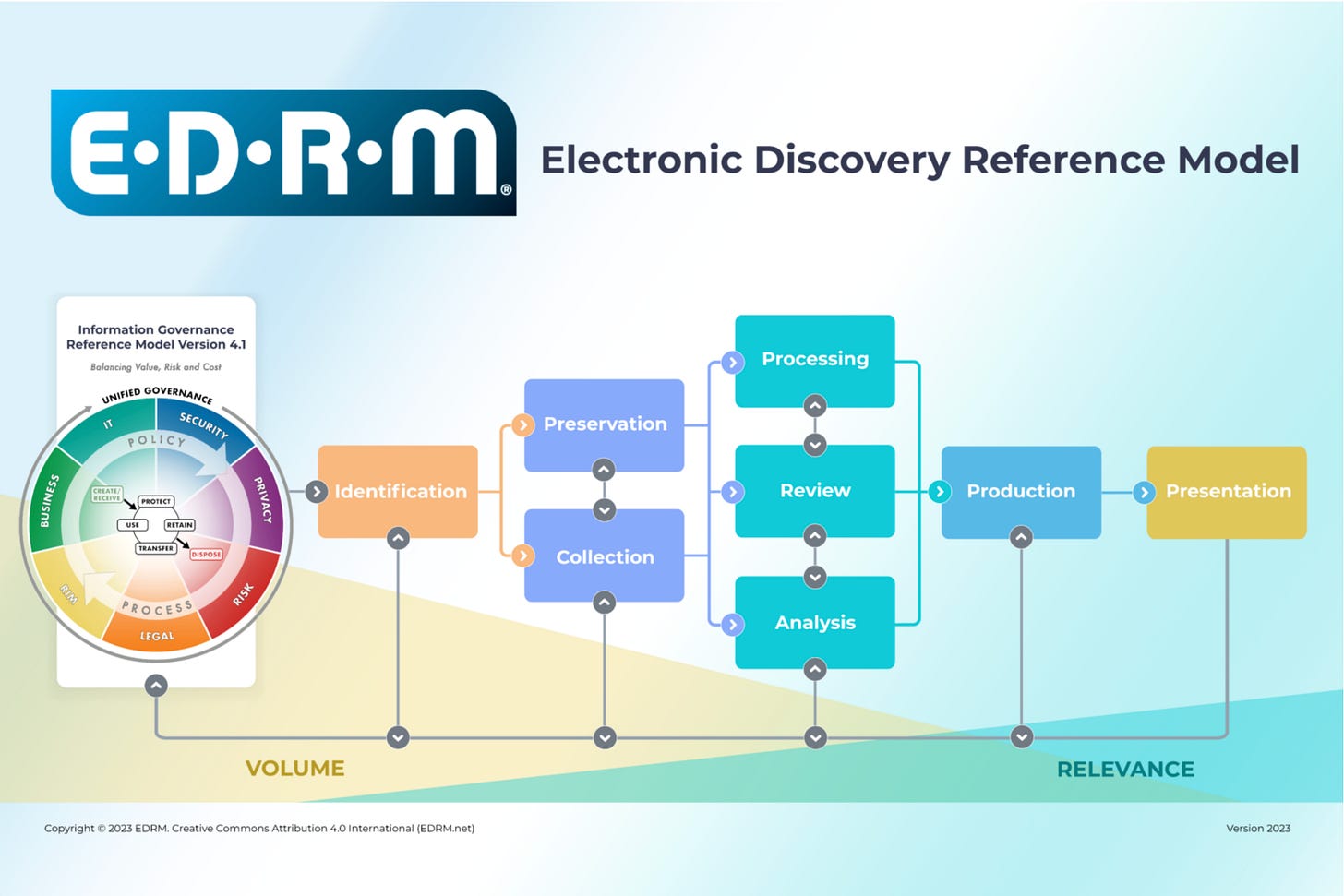

Electronic discovery (e-discovery) is the legal process of identifying, collecting, and producing electronically stored information (ESI) as evidence in a lawsuit or investigation. While traditional discovery involves exchanging physical paper or digital documents, e-discovery focuses exclusively on digital data.

Most legal professionals follow the Electronic Discovery Reference Model (EDRM) to manage the process in a “defensible” manner that stands up in court:

Information Governance: Managing data from its creation to its destruction to reduce risks before a legal matter even begins.

Identification: Pinpointing which digital files are relevant to the case and identifying the “custodians” or people who own or control them.

Preservation: Issuing a legal hold to ensure data is not deleted, altered, or overwritten.

Collection: Gathering the data from sources like email servers, cloud drives, and mobile devices while keeping their original “digital fingerprint” (metadata) intact.

Processing: Converting files into a searchable format and removing duplicates (de-duplication).

Review: Examining the data to decide what is relevant to the case and what should be kept private (attorney-client privileged).

Analysis: Looking for patterns, key topics, and timelines to help build a legal strategy.

Production: Formally delivering the relevant data to the opposing side in a readable format, such as a PDF or native file.

Presentation: Displaying the final evidence to stakeholders (e.g., a judge or jury during a trial or deposition).

7.1 - Understand and comply with investigations

Evidence collection and handling

Proper evidence collection and handling are important for any investigation and are considered the “lifeline of credibility,” especially as digital data now appears in a high percentage of criminal cases.

Because digital evidence is fragile and easily altered, strict collection and handling protocols serve several critical functions:

The primary goal of evidence handling is to ensure that it maintains the Chain of Custody. Maintaining a chronological record of who handled the evidence, when, and why is an absolute requirement for the court. Any “break” or missing link in this chain can lead to a ruling of inadmissible evidence, potentially resulting in the dismissal of an entire case. Chain of custody includes:

Description of the evidence and the circumstances around its collection.

Time and date it was collected.

Exact location of where the evidence was collected.

Name of people collecting the evidence, and logging of who handled it, or transferred it, and why.

Proving that it has not been altered.

Proper handling allows investigators to prove that the evidence presented in court is exactly the same as what was originally collected and has not been tampered with.

Digital evidence is “volatile,” meaning it can be changed accidentally just by turning on a device or copying a file, so maintaining evidence integrity is the primary concern.

Forensic Imaging: creating a "bit-for-bit" duplicate (forensic image) of the original data.

Cryptographic Hashing: Every piece of digital evidence is assigned a "digital fingerprint" or hash value. If even one bit of the data is changed, the hash value changes, alerting investigators to tampering.

Evidence admissibility requirements include the following:

Admissible: It must meet legal rules before it can be introduced in court.

Relevant and Complete: The evidence must be relevant to determining a fact in the case.

Authentic and Related: Evidence must be material or related to the case.

Reliable: Evidence must be competently or legally obtained.

Believable and Convincing: It must be readily believable and understandable by a court.

The International Organization on Computer Evidence (IOCE) established five core principles to ensure that digital evidence is handled reliably and legally admissible:

Integrity (No Alteration): When seizing digital evidence, no actions should be taken that change the original evidence.

Forensic Competence: If it is necessary for someone to access the original digital evidence, that person must be specifically trained and forensically competent to do so.

Full Documentation: Every activity related to the seizure, access, storage, or transfer of digital evidence must be fully documented and preserved so it is available for review by other parties.

Individual Responsibility: Any individual who has digital evidence in their possession is personally responsible for all actions taken with that evidence during that time.

Agency Compliance: Any agency responsible for seizing, accessing, storing, or transferring digital evidence is responsible for ensuring all these principles are followed by its staff.

The Order of Volatility (OoV) determines the sequence for collecting evidence, prioritizing data that is most likely to change or disappear quickly. Based on RFC 3227 guidelines, the standard order from most to least volatile is:

CPU/Cache/Registers: These contain the most transient data, potentially existing only for nanoseconds. They change constantly with every processor cycle.

Memory, Kernel/Routing/ARP Cache/Process Tables: Includes machine RAM and dynamic system data like active network routing tables and kernel statistics that change as the system operates.

Temporary File Systems/Swap Space: Temporary files and swap/page files reside on disk but are frequently modified or overwritten by the operating system during a live session.

Disk (Fixed Storage): Data on physical disks is non-volatile and persists after power-off, though it still risks being overwritten by continued use.

Remote Data: This includes live connections, logs, and monitoring data stored on external servers or cloud services, which may be overwritten by the logging system over time.

Physical Configuration/Network Topology: Physical machine configuration and topology of the network.

Stored Data on Backup Media: Archival media or offline backups are the least volatile, as the data remains unchanged unless the physical media is damaged or intentionally modified.

In legal proceedings, evidence is generally categorized into four primary types based on its nature and how it is presented to the court:

Real Evidence (Physical Evidence): This refers to tangible objects that were directly involved in the event being investigated. Because these items are physical, they can be inspected by the judge or jury.

Documentary Evidence: This consists of information recorded in a format that can be preserved and read, used to prove or challenge facts. Some examples include contracts, emails, business records, and system logs.

Testimonial Evidence: This is oral or written evidence provided by a witness under oath. It involves the witness narrating what they saw, heard, or experienced firsthand.

Demonstrative Evidence: This category includes items created specifically for the trial to illustrate or explain other evidence and testimony. Unlike real evidence, it was not part of the original event but helps the jury understand complex facts.

In legal and forensic contexts, evidence is further classified by source, reliability, and relationship to the facts of the case:

Best Evidence (Primary): The most reliable form of evidence, typically the original document or file rather than a copy or printout.

Secondary Evidence: Evidence that is reproduced from an original source, such as document copies or a witness’s oral description of a document’s contents. This form of evidence is used when best or primary evidence can’t be obtained.

Direct Evidence: Evidence that proves a fact directly without needing any inference or interpretation, such as eyewitness testimony or a video recording of an event or act.

Conclusive Evidence: Evidence so strong that it cannot be contradicted by other evidence. It obliges the judge or jury to reach a specific conclusion.

Circumstantial (Indirect) Evidence: Evidence that suggests a fact by proving other related facts. It requires the judge or jury to make a logical inference to connect the evidence to the conclusion.

Corroborative Evidence: Additional evidence of a different character that strengthens, supports, or confirms already existing evidence.

Opinion Evidence: Testimony provided by a witness regarding what they believe or infer about a fact, rather than what they personally saw or heard. Typically, this type of evidence is limited to expert witnesses with specialized knowledge in a relevant field.

Hearsay Evidence: “Second-hand” evidence consisting of a statement made outside of court by someone other than the person testifying, offered to prove the truth of what was said. It is generally inadmissible unless it meets specific legal exceptions.

Methods of evidence collection are governed by legal frameworks to ensure that evidence is gathered legally and remains admissible in court.

Methods for collecting evidence include:

Voluntary Surrender (Consent): A person with authority over the property or data voluntarily agrees to provide it to investigators. For this to be valid, consent must be given freely, without coercion, and the person can typically limit the scope of what is searched.

Subpoena: A legal demand for an individual or entity (like a business or witness) to produce specific documents, records, or digital data at a later date. Unlike a warrant, a subpoena does not require a showing of probable cause, and the recipient can challenge it in court before complying.

Search Warrant: A court order signed by a judge that authorizes law enforcement to immediately enter a location and search for specific items or data based on probable cause. Warrants for digital devices must often include specific “search protocols” to prevent overly broad or intrusive exploration of private data.

Seizure of Visible Evidence (Plain View Doctrine): This allows officers to seize evidence without a warrant if they are lawfully present (e.g., executing a different warrant or during a traffic stop), the item is in plain sight, and its incriminating nature is immediately apparent. However, while this may allow the seizure of a computer or phone, it generally does not grant the authority to search the digital contents without an additional warrant.

Exigent Circumstances: Emergency situations that allow for immediate warrantless search or seizure to prevent the imminent destruction of evidence, protect lives from immediate danger, or during the “hot pursuit” of a suspect. Once the immediate emergency is over, a warrant is typically required to conduct further detailed searches.

Remember the Locard exchange principle: whenever a crime is committed, something is taken, and something is left behind. In short, contact leaves traces, whether it happens in the physical world or between digital objects.

Reporting and documentation

Reporting and documentation are prioritized as the primary defense against legal challenges and the key to organizational recovery. Effective investigation management centers on these core concepts:

1. Meticulous Step-by-Step: Documentation should serve as a detailed diary of the investigation to ensure it is thorough and fair.

2. Structured Report Creation: A professional investigative report summarizes findings objectively and prompts necessary action.

3. Secure Storage Systems: Integrity is non-negotiable, and investigators rely on secure, centralized systems to protect sensitive data.

4. Stakeholder Updates: Communication must balance transparency with the need to protect the investigation’s integrity.

Investigative techniques

Whether in response to a crime or incident, an organizational policy breach, or troubleshooting a system or network issue, digital forensic methodologies can assist in finding answers, solving problems, and, in some cases, help successfully prosecute crimes.

The forensic investigation process should include the following:

Identification and securing of a crime scene.

Proper collection of evidence that preserves its integrity and the chain of custody.

Examination of all evidence.

Further analysis of the most compelling evidence.

Final reporting.

Sources of information and evidence include:

Interviews, oral/written statements: Statements from witnesses, investigators, or testimony in court by people who witness a crime or who may have pertinent information.

Data collection: Documentation such as business contracts, system logs, network traffic, and other collected system data. This can include photographs, video, recordings, and surveillance footage from security cameras.

Several investigative techniques can be used when conducting analysis:

Forensic analysis: analysis of systems and components that are in scope for the incident or investigation.

Software analysis: focuses on applications and malware, determining how it works and what it’s trying to do, with a goal of attribution.

Third-party collaboration: assistance and collaboration with external organizations and authorities, such as law enforcement or insurance-related external investigators.

Digital forensics tools, tactics, and procedures

Digital forensics leverages highly specialized tools and standardized procedures to address the explosive growth of volatile, distributed data. Key areas of focus for investigators include:

1. Evidence Preservation (The Foundation)

Preserving data integrity is the most critical first step to ensure evidence is legally admissible.

Tactics & Procedures:

Write Blockers: Using hardware write blockers when connecting to storage media prevents inadvertent modification of original data.

Forensic Imaging: Creating “bit-for-bit” duplicate copies of the original media. Analysis is performed only on these working copies, never the original.

Chain of Custody: Maintaining a meticulous, timestamped log of every person who handled the evidence.

Physical Protection: Protecting physical devices from access or damage. Examples include using a Faraday bag to block signals and prevent remote wiping of mobile devices.

2. In-Memory (RAM) Analysis

Memory forensics is essential for detecting “fileless” malware, active network connections, and encryption keys that do not exist on a storage drive.

Key Tools: Memory forensic tools focus on acquiring volatile RAM snapshots and analyzing them for threats. The Volatility Framework (an open-source tool written in Python) is an example.

Tactics: Prioritize RAM capture over hard drive imaging during initial triage because memory is the most volatile evidence and much faster to acquire.

3. Media Analysis (Fixed & Removable Storage)

Media analysis involves deep-level inspection of file systems, registry artifacts, and deleted content.

Key Tools: Media analysis forensic tools provide acquisition, analysis, and reporting capabilities across cloud, desktop, and mobile devices.

Tactics:

File Carving: Recovering fragments of deleted files by searching for specific file signatures in unallocated space.

Artifact Analysis: A specialized digital forensic process of identifying, extracting, and interpreting "digital footprints” or records of activity left behind on a device.

4. Network Forensics

Network analysis captures and reconstructs data flowing through a network to identify attack vectors and data exfiltration.

Key Tools: Examples include Wireshark (packet sniffing), tcpdump, Snort (IDS logs), and Nagios.

Tactics:

Packet Analysis: Deep inspection of individual data packets to identify malicious payloads.

Log Examination: Correlating traffic patterns with system and application logs to build a timeline of the incident.

5. Emerging Trends

Cloud Forensics: Investigators can use specialized tools to extract evidence from remote cloud services and synchronized mobile apps.

AI-Driven Analysis: AI tools are used to automatically flag relevant patterns and anomalies in massive datasets that would take human examiners months to review manually.

Anti-Forensics Countermeasures: Investigators can use techniques like Metadata Analysis to detect when cybercriminals have attempted to wipe or manipulate evidence.

Artifacts (e.g., data, computer, network, mobile device)

Digital artifacts or digital evidence that provide information on a security incident are classified by their source and state (e.g., volatile vs. non-volatile). These "remnants" allow investigators to reconstruct who performed an action, what occurred, and when it happened.

Examples of artifacts include:

Computer & OS: artifacts that track user activity, program execution, and system configuration, such as Windows registry elements, execution remnants (proof a program was run), or event logs.

Network: Traffic telemetry, and connection logs that track data movement and external communications.

Mobile device: Smartphones function as "digital journals" with unique location and communication data that might include SMS, GPS location data, or browser history.

7.2 - Conduct logging and monitoring activities

Logging and monitoring are the primary mechanisms for security assurance, shifting security from a reactive "snapshot" approach to an ongoing "operational cadence". They help prevent incidents and provide critical validation that security controls, such as access management, firewalls, and encryption, are functioning as designed and effectively protecting assets.

Logging simply means recording information about events, such as changes, messages, and activities. The goal is to keep a record of what, when, where, and even how an event occurred. Logging and monitoring act as an "electronic sentry," providing immediate visibility when a control is bypassed or incorrectly implemented.

Security professionals need to understand and master tools such as IDPS, SIEM, SOAR, Threat Intelligence, and UEBA because modern cyberattacks, now frequently accelerated by AI, unfold faster than manual monitoring can keep pace. These technologies work together to transform massive volumes of raw data into actionable security insights and rapid responses.

Sampling is a technique for managing the explosive volume of telemetry data generated by distributed systems and AI-driven infrastructures. By capturing and analyzing a representative subset of data rather than every event, organizations can maintain visibility while controlling costs.

Clipping levels are a form of non-statistical (or discretionary) sampling in which only events that exceed a predefined threshold (the clipping level) are selected, and these types of events are ignored until they reach this threshold. Clipping is widely used to set a baseline for user activity or routine events.

Intrusion detection and prevention (IDPS)

IDPS provides early warning signals by monitoring network traffic for known threats or policy violations in real time. The technology helps provide visibility into malicious activity across networks with both real-time alerting (IDS) and automated response (IPS).

The two primary detection methodologies differ in their approach to identifying threats:

1. Signature-Based

Signature-based (AKA pattern-based or knowledge-based) IDPS works like antivirus software, matching incoming traffic against a database of known attack patterns or “signatures.”

Effectiveness: Highly accurate at detecting known threats.

Key Advantage: It produces a very low false-positive rate, meaning it rarely flags legitimate traffic as a threat.

Limitation: It is entirely ineffective against zero-day exploits or novel attacks that do not yet have a recorded signature.

2. Anomaly-Based

Instead of looking for specific threats, this method establishes a normalized baseline of typical network behavior and flags any significant deviations as suspicious.

Effectiveness: It excels at detecting unknown or emerging threats, including zero-day attacks, sophisticated insider threats, and polymorphic malware.

Key Advantage: It is highly adaptable and can identify unusual patterns (e.g., massive data transfers at 3 AM) that signature-based systems would miss.

Limitation: It is prone to a higher false-positive rate because legitimate but unusual business changes can trigger alerts. It also requires substantial computational resources for real-time behavioral analysis.

Security Information and Event Management (SIEM)

A SIEM collects, aggregates, and analyzes log and event data from various sources across an IT environment, such as network hardware, applications, and endpoints.

SIEMs have evolved from simple log collectors into “central nervous systems” for Security Operations Centers (SOCs), prioritizing threat detection, investigation, and response over basic compliance.

Common SIEM features include:

Data aggregation and normalization: Collects logs from diverse sources (firewalls, cloud apps, servers) and converts them into a uniform, searchable format.

Real-time event correlation: Uses predefined rules and advanced analytics to link seemingly unrelated log events (e.g., a failed login followed by a successful one from an unusual location) to identify a single multi-stage threat.

AI and machine learning: Employs advanced algorithms to detect anomalies and “fileless” attacks that traditional signature-based rules might miss.

User and Entity Behavior Analytics (UEBA): Establishes behavioral baselines for users and devices to flag suspicious deviations, such as an employee accessing sensitive files at odd hours.

Incident response automation integration: Modern platforms increasingly integrate Security Orchestration, Automation, and Response (SOAR) to trigger automated workflows, such as isolating a compromised host or blocking a malicious IP within seconds.

Compliance Management and Reporting: Automates the creation of audit-ready reports for regulatory frameworks like GDPR, HIPAA, and PCI DSS.

Centralized dashboards: Provide “single-pane-of-glass” visibility with visual metrics and real-time alerts for security analysts.

Forensic and historical analysis: Enables teams to search vast amounts of historical data to reconstruct the timeline of an attack and find its root cause.

Threat intelligence integration: Enriches internal log data with external feeds of global indicators of compromise (IoCs) for more accurate detection.

Security Orchestration, Automation, and Response (SOAR) is a technology stack that enables organizations to collect data from various security sources, such as firewalls and endpoint protection systems, and automate responses to security events through a centralized platform.

SOAR is critical for reducing "alert fatigue" by automating low-level, repetitive tasks, allowing security analysts to focus on complex threat hunting and investigation.

Playbooks vs runbooks: note that there isn’t a universal definition for these terms. However, in incident response, playbooks are broad documents, checklists, or digital workflows that outline the high-level plan for responding to specific incident types. They help coordinate security tools and personnel to ensure a consistent, organization-wide response. Playbooks are the documented processes that should be followed.

Runbooks, on the other hand, implement the playbook’s actions. In a SOAR context, runbooks take playbook steps and translate them into automated actions and workflows. Runbooks are the implementation of the playbook’s documented processes.

Continuous monitoring and tuning

Monitoring and tuning are continuous processes of assessing events and adjusting security controls to match an organization’s requirements and operating environment. Systems like IDPS require tuning to reduce false positives while ensuring that potential intrusions are not missed.

In order to maximize the value of monitoring and tuning, considerations include:

Establish metrics and KPIs: As we’ve previously noted, metrics are important for establishing baselines and showing progress, especially in the context of event and control monitoring. Boards will continue to require quantified, data-driven insights that metrics help provide.

It’s also important to continuously improve security operations via processes such as root cause analysis, maintaining updated policies, and continuous training, evaluation, and tuning.

Egress monitoring

Egress monitoring involves tracking and analyzing data as it leaves a private network for external destinations. While many organizations traditionally focus on "ingress" (incoming) traffic to block external attacks, egress monitoring focuses on the internal-to-external flow to prevent data loss and detect compromised systems already inside the network.

The goal of egress monitoring is to prevent the exfiltration of sensitive data, disrupt malware, detect early compromise, and monitor the sharing of personal or financial information.

Egress monitoring tools and considerations include:

Developing policies and rule sets to detect and deter exfiltration and communication with known malicious sites and services.

Using egress filtering and monitoring controls such as firewalls and data loss prevention (DLP) to detect and block sensitive data transmissions and provide alerting.

Using modern firewalls that can inspect the content of encrypted outbound traffic to ensure sensitive files are not hidden within authorized protocols like HTTPS.

Monitoring egress traffic from internal services to third-party APIs to prevent the leakage of PII or the abuse of API keys.

Integrating egress monitoring with other tools such as SIEM and SOAR.

Log management

Log management captures, stores, and protects the logs generated across an organization’s infrastructure. Robust log management is a requirement to support security monitoring, incident response, and compliance.

Log management involves creating the systems and infrastructure to capture and store log data from an organization’s diverse and relevant sources. To avoid losing data, organizations capture logs from the full stack, including ephemeral sources such as serverless functions and containers.

Log data should be stored for relevant periods, and retention and archival policies should define:

The availability of log data for required record retention and regulatory compliance.

The integrity of log data, for instance, by storing logs in a centralized location and ensuring that logs have not been altered or deleted.

Ensuring the confidentiality of log data, which often contains sensitive information, such as IP addresses, usernames, and sometimes inadvertently captured passwords or PII.

Threat intelligence (e.g., threat feeds, threat hunting)

Threat intelligence is the collection, analysis, and interpretation of information about potential or current attacks targeting an organization. It can be classified into three functional levels:

Strategic Intelligence: High-level information for executives and board members regarding long-term trends, geopolitical risks, and financial impacts.

Operational Intelligence: Detailed insights into specific incoming campaigns, including the “who” (threat actors) and “why” (motivations) behind an attack.

Tactical Intelligence: Real-time, technical indicators of compromise (IoCs) like malicious sites, IP addresses, file hashes, and specific Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) used by attackers.

A threat intelligence feed is an automated, continuous stream of real-time data that provides actionable information on emerging and active cyber threats. These feeds are the "breaking news ticker" for cybersecurity teams, delivering the technical details needed to identify and block attacks before they impact an organization.

STIX and TAXII are the global open standards that enable organizations to share cyber threat intelligence in a machine-readable format, reducing the need for manual data processing.

STIX (Structured Threat Information eXpression) is a standardized language and serialization format, typically in JSON, for describing cyber threat information.

TAXII (Trusted Automated eXchange of Intelligence Information) is the transport protocol used to securely exchange STIX-formatted data over HTTPS.

Automated Indicator Sharing (AIS) is a no-cost, voluntary service that enables the real-time exchange of machine-readable cyber threat indicators and defensive measures between the federal government and the private sector. AIS is managed by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

Threat hunting is a proactive search across an organization’s network and endpoints to identify malicious activity that has evaded traditional automated security tools. Unlike reactive monitoring, which waits for a system alert to trigger an investigation, threat hunting assumes an attacker may already be present in the environment.

The Cyber Kill Chain is a foundational cybersecurity framework that describes the sequential stages an adversary must complete to conduct a successful attack. Developed by Lockheed Martin, it adapts military strategy to help defenders identify, disrupt, and prevent intrusions across the attack lifecycle.

While some modern models expand this to eight stages by adding monetization (how attackers profit), the classic Lockheed Martin model consists of seven phases:

Reconnaissance: Gathering intelligence on the target, such as identifying open ports, searching employee details on social media, or scanning for network vulnerabilities.

Weaponization: Coupling an exploit (targeting a specific vulnerability) with a malicious payload that includes a backdoor for delivery to the target.

Delivery: Transmitting the weaponized payload to the target via phishing emails, malicious links, compromised websites, or physical media like USB drives.

Exploitation: Executing the malicious code on the target system by taking advantage of a software or hardware vulnerability.

Installation: Establishing a persistent foothold on the victim’s network, often by installing backdoors or Trojans that survive system reboots.

Command and Control (C2): Establishing a remote communication channel between the compromised system and the attacker’s infrastructure to receive instructions or move laterally.

Actions on Objectives: The final phase, where the attacker fulfills their primary goal, such as exfiltrating data, destroying systems, or encrypting files for ransom.

By understanding these phases, defenders can aim to "break the chain" as early as possible. Disrupting even a single stage can prevent the entire attack from succeeding. Security teams use the kill chain to map specific controls to each phase (e.g., email security for Delivery, EDR for Exploitation, and network monitoring for C2).

While traditionally linear, it is increasingly used alongside more detailed frameworks like MITRE ATT&CK to handle non-linear, AI-accelerated attacks that may compress multiple stages into hours rather than weeks.

MITRE ATT&CK (Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge) is the global industry-standard knowledge base for documenting and categorizing real-world cyber adversary behaviors. It provides a standardized language that allows security professionals to describe "how" and "why" attackers operate.

The framework or core is structured into tactics, techniques, sub-techniques, and procedures (TTPs):

Tactics (The “Why”): The high-level technical goals an adversary wants to achieve, such as initial access, persistence, or exfiltration.

Techniques (The “How”): Specific methods used to achieve a tactic. For example, spearphishing attachment is a technique used to achieve the Initial Access tactic.

Sub-techniques (The “How” in Detail): More granular descriptions of a technique. Under phishing for instance, sub-techniques might include spearphishing link or “Spearphishing via Service.”

Procedures: Real-world implementations and specific tools used by threat actors in observed incidents.

User and Entity Behavior Analytics (UEBA)

UEBA is an advanced cybersecurity solution that often uses AI and ML to establish "normal" behavioral baselines for users and entities. By monitoring for deviations from these baselines, UEBA identifies subtle, risky activities that traditional rule-based security tools often miss.

Behavioral Baselining: The UEBA system observes activity over a period of time to learn patterns using data collected from sources such as system, application, and endpoint logs. The baseline covers things like standard login times, frequent file access, and average data transfer volumes.

Anomaly Detection: Once a baseline is established, it continuously compares real-time activity to these norms. For example, a user who typically downloads 20MB of data suddenly downloading 4GB might be flagged as an anomaly.

Dynamic Risk Scoring: UEBA assigns a risk score to each anomaly based on its severity and context. Multiple minor anomalies (e.g., a login from a new location plus access to sensitive files) can aggregate into a high-risk score that triggers an alert.

UEBA use cases include areas such as:

Insider Threat Detection: Identifies unusual behavior that might indicate policy violations or malicious intent to harm the organization.

Compromised Account Identification: Detects when a legitimate user’s credentials have been stolen by highlighting behavioral changes, even if the login appears authorized. It also helps monitor highly privileged user accounts for IoCs.

Zero-Day and APT Detection: Uncovers sophisticated “low and slow” attacks and previously unknown exploits that lack traditional signatures.

Data Exfiltration Prevention: Monitors for unusual data movement, such as large transfers to external cloud services or USB drives.

7.3 - Perform Configuration Management (CM) (e.g., provisioning, baselining, automation)

Configuration Management (CM) is the process of identifying, controlling, and verifying the configuration of organizational systems and settings. The focus is on establishing and maintaining the integrity of IT products and systems by controlling their initialization and changes, and by monitoring configuration throughout their lifecycle.

When something changes in systems under configuration management, for instance, patching software or a configuration update, the change is recorded. This allows the configuration management system to track changes, helping prevent mistakes and reduce security risks.

Some of the core functions of configuration management include:

Developing a configuration management plan that outlines roles, responsibilities, standards, and the tools to be used for a project.

Selecting and documenting configuration items (any IT asset worth tracking) and establishing a baseline configuration snapshot.

Implementing configuration change control, a structured process managed by a configuration control board to review, approve, and track system changes to prevent unauthorized or risky modifications.

Record-keeping that documents details (location, version, status) and tracks the history of changes (who, what, when, and why).

Formal reviews to ensure that a system actually matches its design documentation and satisfies established performance and security requirements.

Provisioning means taking a specific config baseline, creating additional or modified copies, and deploying those copies into the environment. For instance, installing and configuring the operating system and required applications on new systems.

System hardening refers to the process of applying security configurations and locking down hardware, communication systems, and software. System hardening is normally based on industry guidelines and benchmarks.

A baseline in the context of configuration management is the starting point or starting config for a system.

7.4 - Apply foundational security operations concepts

Need-to-know/least privilege

Need-to-Know is a fundamental security principle that restricts access to sensitive data to only those individuals who require it to perform their specific, authorized job duties. It ensures that a user must have a legitimate business or mission requirement to access specific information, and even if an individual has the appropriate security clearance or high-level organizational role, they are still denied access to data that is not essential for their current task.

Granular data-centric access controls are often applied to specific information or data sets, which can be challenging to enforce in hybrid environments.

As we discussed in Domain 3, least privilege means that subjects are granted only the privileges necessary to perform assigned work tasks and no more. The concept should be applied to data, software, and system design to reduce the surface, scope, and impact of any attack.

Separation of Duties (SoD) and responsibilities

Separation of Duties (SoD) (AKA Segregation of Duties) helps prevent any single person from having enough unchecked authority to commit and conceal fraud or errors by dividing tasks among different individuals or organizations. It’s an effective "system of checks and balances," and a primary defense against insider threats.

Collusion is an agreement or cooperation between two or more individuals to deceive, bypass security controls, or commit fraud. By splitting responsibilities, SoD reduces the likelihood of fraud because it requires collusion — multiple people working together to commit the crime.

Privileged account management

Privileged Account Management (PAM) is the specialized security around controlling, monitoring, and auditing accounts with elevated permissions. These accounts have the authority to perform critical tasks like changing configurations, installing software, or accessing sensitive data.

PAM combines people, processes, and technology to tightly control who can access privileged accounts and how they’re used, helping protect an organization’s most critical systems and data. PAM enforces least privilege by granting only the minimum access needed for a role. It can also provide Just-in-Time (JIT) access, granting elevated privileges temporarily for a specific task and automatically revoking them once the task is complete, eliminating "standing privileges."

PAM is often required to qualify for cyber insurance and to meet stringent regulatory requirements.

Job rotation

Job rotation is an administrative security control where employees are systematically moved through different positions or tasks within an organization at regular intervals.

While it is often used for cross-training and employee development, its primary purpose in security is to act as a detective and deterrent control against fraud and insider threats.

As a real-world example, rotating the administrators responsible for managing the PAM system ensures that no single “super-admin” has unchecked control over the organization’s most sensitive credentials for too long.

Service-level agreements (SLA)

A service-level agreement (SLA) is a legally binding contract between a service provider and a customer that defines the expected service standard, the metrics used to measure it, and the remedies available if those standards are not met.

Effective SLAs often include several essential elements to prevent ambiguity:

Service Description: A detailed overview of exactly what services are provided, their scope, and any dependencies.

Performance Metrics: Quantifiable criteria (KPIs) such as uptime percentages, response times, and resolution rates.

Roles and Responsibilities: Clear definitions of what is expected from both the provider and the customer (e.g., the customer’s duty to report issues promptly).

Penalties and Rewards: Financial consequences like service credits for missed targets, or occasionally incentives for exceeding performance standards.

Exclusions: Explicitly stated services or circumstances (like natural disasters or “force majeure”) that are not covered by the agreement.

Security and Compliance: Protocols for data protection, confidentiality, and meeting industry-specific regulatory standards (e.g., HIPAA for healthcare).

In part two, we’ll continue through Domain 7 and objectives 7.5 forward. If you’re on the CISSP learning journey, keep studying and connecting the dots, and let me know if you have any questions about this domain.