Risk Concepts From The CISSP (Part 3)

Applying Risk and Risk Management Practices In Your Organization

Introduction

“How cybersecurity assesses risk, and how it determines how much it reduces risk, are the basis for determining where cybersecurity needs to prioritize the use of resources. And if this method is broken—or even just leaves room for significant improvement—then that is the highest-priority problem for cybersecurity to tackle!”

— How To Measure Anything in Cybersecurity Risk (Hubbard and Seiersen)

In our previous articles, Risk Concepts from the CISSP (Part 1) and (Part 2), we covered the (ISC)² risk terminology, methods for gauging an organization's risk appetite, and assessing threats and risks. We also described how to enumerate risks using qualitative and quantitative measures representing risk factors.

From our risk assessment work, we now have a list of factors and estimated quantitative values (and likely a list of scenarios of risk possibilities). The question is, what do we do with this information? In part 3, we look at possible responses to the identified risks, evaluating the cost/benefit, category, and types of controls, and we discuss risk reporting.

Risk Response

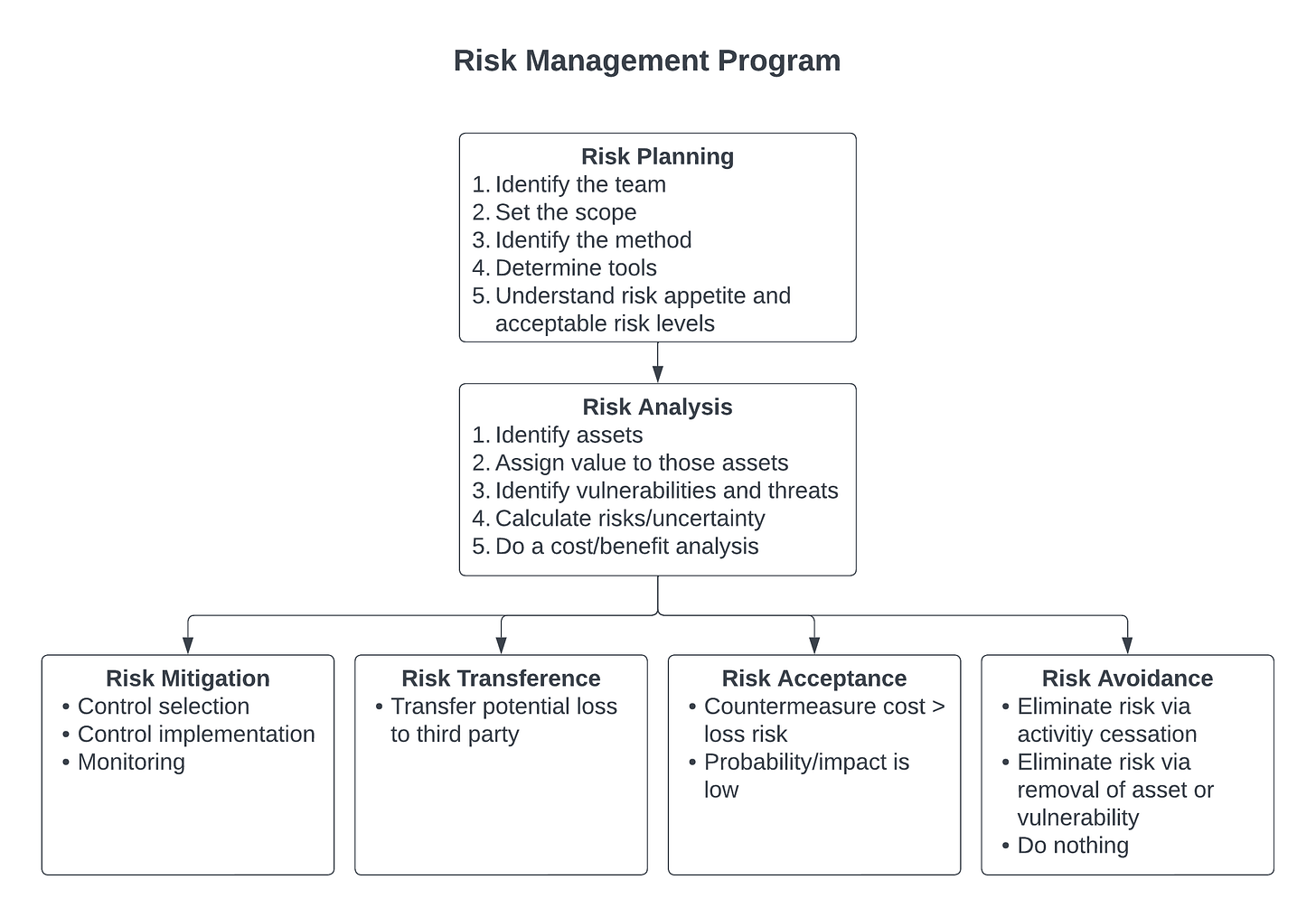

Let's take a step back from where we've been, look at what we've accomplished, and think about the next phase in our process. Our work so far has been to plan our approach to risk management by identifying the team, creating a plan, and setting the scope of what we want to accomplish. We identified the tools we wanted to use and the risk appetite of our organization. We completed a risk analysis that included identifying the organization's assets, assigning a value to each asset, identifying vulnerabilities and threats, and calculating risks. We now need to do a cost/benefit of our potential threat mitigations. These steps and those that follow are shown in Figure 1 below.

Note that using a hybrid method of a quantitative approach for tangible assets and a qualitative one for those that are non-tangible can help maximize the advantages of each. The output of our qualitative and quantitative risk analysis includes:

Monetary values assigned to assets

A comprehensive list of significant threats

Our compiled list includes a probability of occurrence for each threat, and loss potential for tangible assets (from our quantitative list)

A list of possible risk scenarios for our non-tangible assets, ranked by the seriousness of the threat (from our qualitative list).

Our analysis gives us a better understanding of the total risk to the organization. We implement countermeasures as a means of reducing risk to an acceptable level, however, keep in mind that no environment is 100% secure, and we will always have some leftover or residual risk. You can think of this conceptually as residual risk = total risk - countermeasures. Because no environment is completely secure, and no organization can remove every threat, there will always be residual risk. This is the idea that leads us to consider what level of risk an organization is willing to accept (also known as risk appetite).

There are four basic responses to risk: transfer it, avoid it, reduce it, or accept it. There are many types of insurance available to protect assets, and purchasing insurance coverage is a method of transferring risk to the insurance company. If, after analyzing risk, the organization determines that the best plan is to cease a particular activity, this is a method of risk avoidance. The implementation of intrusion/detection systems, firewalls, training, or other types of controls helps reduce risk. This is known as risk mitigation. The final category of risk response is risk acceptance, which means that after analyzing and understanding the level and potential damage from a particular risk, the organization decides to not implement a countermeasure and simply live with it.

Selecting Countermeasures

Once we know the amount of total risk, we need to decide how to handle it. Risk mitigation is the most common approach to risk treatment and involves the implementation of one or more countermeasures. We can use a cost/benefit analysis to measure the cost-effectiveness of a particular safeguard/control.

Remember that Annualized Loss Expectancy (ALE), or the yearly potential loss of a specific realized threat against an asset, is the product of Single Loss Expectancy (SLE) times the Annualized Rate of Occurrence (ARO). The cost/benefit analysis formula for a given countermeasure is computed as follows:

(ALE before countermeasure) - (ALE after countermeasure) - (annual cost of countermeasure) = Value of countermeasure or safeguard to the organization

As an example, assuming we are concerned about the specific threat of data loss, and through our analysis (covered in Part 2), we determine the ALE for that particular threat is $100,000. Let's say we implement a cloud-based data backup as our countermeasure, which, when implemented, potentially reduces our ALE to $10,000 (note: introduction of our countermeasure doesn't necessarily reduce our loss expectancy to zero because if we incur data loss, we may still have a period, during recovery, when data is unavailable). If the cost of our countermeasure is $10,000 (comprised of time spent setting up the process and cloud data storage charges), the value of the countermeasure to the organization is $80,000/year.

Because the ALE includes two factors, the single loss expectancy and the annual rate of occurrence, the safeguard can decrease either or both. In the example above, the introduction of a cloud data backup service may simply reduce the costs of restoring data that was unexpectedly lost. Other countermeasures may be targeted at actually reducing the likelihood of that loss. While we often focus on threat reduction, it may be less expensive in some cases to make it easier to recover an asset after a loss.

Note that the cost of a countermeasure is usually much more than the purchase price. Other costs to consider include design/planning and implementation costs, as well as the costs of ongoing operations, support, and potential impacts on productivity.

Categories and Types of Controls

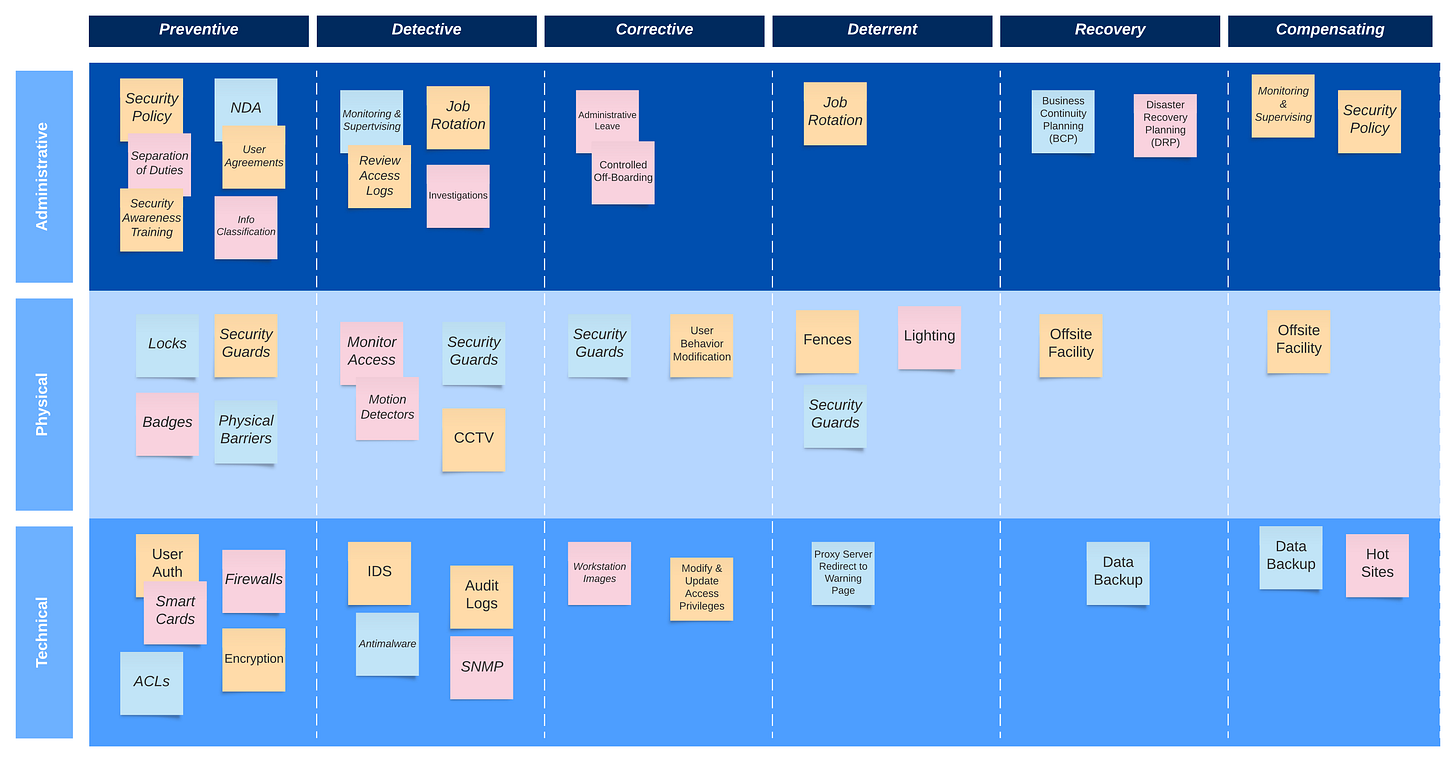

Controls or safeguards can be categorized into three main types: administrative, technical, and physical. Administrative (or “soft”) controls are management oriented. Technical (or logical) controls are software, hardware, encryption, identification, or authorization mechanisms, and physical controls are those put in place to protect people, facilities, or resources.

It's important to remember that different types of controls should be used in a layered approach known as defense-in-depth. A multilayered defense reduces the likelihood of compromise because attackers need to defeat several different types of protection mechanisms. As an example, technical controls commonly used in a layered approach include firewalls, intrusion detection and prevention, anti-malware, access control, and encryption. The types of controls used need to map to the characteristics of the threat and the organization's value of the asset. Usually, the more sensitive the asset, the more layers of protection are warranted.

You can specify different types of security controls for each category (administrative, technical, and physical). The different types of controls are:

Preventive: used to avoid the occurrence of an event

Detective: used to identify an event's activities

Corrective: used to fix a system or component after an event

Deterrent: used to discourage (or deter) an attack or event

Recovery: used to bring a system or component back to normal operations

Compensating: provides an alternative measure of control

Keep in mind that many controls may fall into multiple classifications, and thinking about the security of an environment, you may consider detective, corrective, and recovery controls to support a preventative model. Figure 2 below shows some examples of control types by category.

Risk Reporting

Risk Reporting is a key task to perform at the conclusion of risk analysis, usually in the form of production and presentation of a summarizing report to stakeholders. Reporting enables organizational decision-making, forms the outline of your security management program, and informs day-to-day operations.

There are three groups that you should consider including in risk reporting: executives and the board, managers, and risk owners. How you report findings may vary by group. For instance, execs and board members are likely not interested in details, they will want to understand the most significant organizational risks and associated mitigation strategies. Reporting for this group should be high-level, well-summarized information that portrays the risk story in a concise manner. Managers will need more detail to put together action plans to manage the identified risks. Risk-management dashboards (or spreadsheets) work well for reporting to this group. Risk owners are staff members responsible for managing individual risks and will need the most detailed reporting to ensure compliance and mitigation.

Summary

The primary goal of risk management is to reduce risk and bring it into alignment with the organization’s risk appetite. Through a risk assessment process, we enumerate assets and risks. From the associated analysis, we can determine our response to each risk/threat pair and perform a cost/benefit review of a particular safeguard/control.

We looked at the categories and types of controls and the idea of layering them to provide several different types of protection mechanisms. We also reviewed the important step of reporting our risk analysis and recommended responses, noting differences in how to report findings by group.

In future posts, we’ll look into continuous improvement, risk maturity modeling and discuss risk frameworks.